Blog

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in the Center of Child Welfare: A 21st Century Perspective on Cultural Relevance and Humility

The pervasive issue of racial disparity in child welfare has long presented troubling implications for children and families of color. The concept of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) is essential in developing inclusive practices that work to dismantle historical and systemic racial biases in the sector. ASCI’s founder, president and CEO Dr. Sharon McDaniel engages in crucial conversations with industry thought leaders to explore DEI in America’s child welfare system and highlight the transformational work these leaders do to address the same.

Installment Two with Joyce James, LMSW-AP

Racial equity consultant

President/CEO, Joyce James Consulting

Dr. Sharon McDaniel: Our hope is to really put diversity and equity inclusion at the center of child welfare. You are, by far, the nation’s leading expert in the space around racial equity. You are certainly, by far, someone I’ve looked up to in terms of this space and your authenticity in how you bring your work, your passion, to the center and how you’re unapologetic about what you do, how you do it and what you say. So, why is this work so important to you?

Joyce James: [I provide] racial-equity technical assistance and support to systems, institutions and community-based organizations that are seeking to transform the culture of their institutions to ensure the best potential for good outcomes for all children, youth and families.

I’m a social worker by profession. I started my career as a frontline Child Protective Services caseworker in southeast Texas. I have had the privilege of working up the career ladder and being able to identify with every position in child welfare [up to] being the head of Child Protective Services for the state of Texas. My work in that arena was very much focused on racial disproportionality and disparities for African-American children, youth and families and in Texas, as well, for Native American children, youth and families. So, as a result of using race equity analysis, I had the opportunity to inform legislation in Texas, and in 2005, Texas became the first state in the country to have laws requiring Child Protective Services to address racial disproportionality.

The outcomes we experienced as a result of doing work through a racial-equity lens and having an analysis of institutional and structural racism led to some unprecedented outcomes for children, youth and families in Texas. That actually led to my appointment at Texas Health and Human Services as the Associate Deputy Executive Commissioner for the Center for the Elimination of Disproportionality and Disparities.

The model in child welfare had been so effective that the executive commissioner wanted to expand the use of that model in race equity analysis across state agencies. So, I did that work across multiple agencies, included leading the State Office of Minority Health for three years. So, I’ve had many years of experience. I do want to say, before we go on to the next piece, that I haven’t always had this analysis. So, I’ve stood in the space where many child welfare leaders stand today—struggling with how to have conversations about race, how to share what it felt like to be restricted to working in ways that went against everything that I valued and believed in. I know that there are people who still have those struggles today, and so I work very hard to try to share my experience—starting back when I didn’t have an analysis and didn’t know how to challenge the system—and my journey to where I am today.

SM: I think we do all arrive in different ways, places and times. Can you talk about that pivotal moment when you recognized, “I don’t have that analysis, and I need to have that analysis”?

JJ: Well, what happened for me started with my very first caseloads. My first job was as an institutional worker. I was responsible for finding placements [for youth] in institutions, state schools and residential treatment facilities. Early on in my career, I had concerns even about my caseload, because it was made up primarily of older black teens. What’s ironic and profound, is that that’s still the case today, almost 40 years later. We still see this same pattern—in particular, African Americans, usually males; but in some spaces, females are disproportionately represented—in those restricted placements.

From day one, I found myself putting kids in my car, traveling long distances across the state of Texas and dropping them off in facilities where I never would have wanted my own children to be. Yet, I didn’t feel like I had a space to complain about it, and as I look back, those facilities were licensed by the state of Texas. So, that was the system’s message to me that it was OK to do that, but it was never OK with me. I didn’t know how to bring my concerns internal. So, I tried to work them out in other ways.

So, we know that there are individuals today who take on the added responsibility of working outside of the system to meet the needs of youth and families. The reason why it’s so important to understand the difference between an individual and an institutional response is because we want that for all children and youth. It won’t be that way unless we create an institutional culture that supports staff in having that understanding of how we work to meet the needs of all our youth, and that we don’t place the burden on individual caseworkers. I used to go out and ask my family and my church members for money so that my youth had hair care and skin care products and to ensure that they had adequate clothes and all of those things that weren’t standard for all children.

It becomes standardized when it operates out of the institutional culture. I carry with me the faces of the children who made up my very first caseload, and I still remember them, and I remember their names, and I know they are adults, probably with children of their own today. But I remember that we failed them unintentionally. I didn’t come to my work to hurt. I had come to help. So, I kept waiting for an opportunity to be able to raise issues around race, and it wasn’t there. So, what we have to do even today is create a liberated space for people to really talk about their experiences inside the institution and about how many well-meaning individuals are oppressed by the institutional culture.

I have to give credit to Casey Family Programs for inviting me to the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond’s Undoing Racism workshop in the ’90s. I had already started looking at data around race and racism as a regional director, but I still didn’t have the analysis. It was actually participating in that workshop when I began to understand how we have been socialized around race. When I say “we,” I mean across racial lines, we have been socialized to see nonwhite people—in particular, black, Hispanic, Latino, Native American populations—as being less than, as being inferior. We have internalized that to the extent that we often act in ways we’re not conscious of. I made the decision in the late ’90s that I had to own that I was silent for a long time. Many of us are oppressed to the extent in institutions that we are silenced. We have to come to develop a language to talk about race and racism and how it impacts [us], but in ways that are not about pointing fingers and laying blame. I’m very intentional about that, but I’m also intentional about saying that it doesn’t matter how well-meaning or how well-intentioned we are, if we’re not race-competent, we continue to do harm.

The evidence of that is in the data, not only in child welfare, but in every system where the same people have the worst of outcomes. It’s all predictable by race, such that even when you make all factors the same, race will predict who will have the best outcomes and who will have the worst outcomes. As I began to bring that analysis to my work as a regional director, we began to see some significant changes in engaging families, engaging the voices of youth, understanding that we had to be willing to be vulnerable and transparent enough to share the data with the communities we were serving.

Such that they felt a genuine inclination to sit at the table with us and to tell us what we needed to do differently to better serve them, because we had been trying to do the reverse, and a lot of people still adhere to that kind of training.

There is no profession that requires its members to have an analysis and an understanding of institutional and structural racism. So, when people come to institutions to work, especially with vulnerable and marginalized communities and even just different races of people, they don’t come with that knowledge. So, if they’re not getting it through academic arenas—you know, higher education—then the institution has to become accountable for ensuring that we are examining attitudes, assumptions and stereotypes that people come with, because of the way we’ve been socialized, before we send them into a community to do damage in ways they are not conscious of.

So, beyond that, I had the opportunity in 2004 to serve as the first African-American director for Texas Child Protective Services, and I say that because, we know that child welfare systems have been in place since the 1930s and that the system was actually designed to serve white children. African-American children moved from being totally excluded, to overly inclusive by the late ’70s, early ’80s. Today, [we’re] seeing them disproportionately represented in every child welfare system in the country. So, when I had the opportunity to go to Austin to lead a state-run program with 254 counties, and to become very conscious of the need to use data to tell the story, one of the first components of the model I developed to do this work was data-driven strategies … we cannot know who is benefiting from our programs and services if we’re not disaggregating the data by race and ethnicity.

Beyond the numbers we get from the data, is the story behind the data. And not only from the people who work inside the system, but from the members of the community, families and children who can tell us what their real experiences are. So, I had the opportunity to implement what is called “The Texas Model for Addressing Disproportionality and Disparities” and started the work before the legislation. The legislation in Texas actually gave us a strong framework, an opportunity to work in ways that we had never worked as a state. There was a requirement in the law that we would train our staff in cultural competency.

I knew it couldn’t be the same cultural-competency training that we had then, because you went on the computer, you checked the boxes, then you completed and printed off a certificate that said you’re culturally competent. For me, it had to be something as profound as having an analysis of racism, and the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond will tell you wherever they go, that we invited them to work inside the institution. When they had been used to doing what Ron Chisholm called “throwing rocks at institutions,” having people coming in and immersing themselves in the kind of conversation that allowed us to develop a racial-equity lens; building programs that were framed around race competency; creating a culture where we elevated our consciousness about how we had been working.

When we become conscious about institutional and structural racism and when well-meaning people can see it, then they are best at saying what we need to do differently … and so, things like caseworkers saying, “Wow, when we used to get calls from communities like that, we would just put the car seat in the car. We already knew it was going be a removal before we got there.” Now, it’s not something that they’ve consciously thought about when they were doing it, but socialization is so powerful that unless we create a space for people to examine those things they think they know, those things they have been socialized to believe for a very long time, there is not a space to question until they can get in touch with that and recognize that a lot of the things we think we know, have no factual basis—like our fear of black communities, like our fear of black men—and how that fear influences whose children get removed, which kinship families we approve, which families get reunited with their children, whose rights are terminated and which fathers we engage.

As I have had an opportunity to do this work with caseworkers across the country and ask them how they’ve been socialized to go into certain communities, they can tell you consistently across the country that they have received either formal or informal messages that they shouldn’t go into certain communities by themselves, that they should not go at night, that they may need to take law enforcement, that they should not wear nice jewelry, that they should put their purses in the trunk, that they should not sit down in the house but stand near an exit … so, if that’s all they know, then who wouldn’t be afraid, right? When you ask, “How does this influence whether or not you want to visit, how long you stay, how quickly you are to remove children, how you testify to the court about what needs to happen in those cases?” … when you can put staff in a space where they can own and examine the validity of those fears and get in touch with them, that’s when you see change start to occur.

SM: As you were talking about training, I’m thinking about my CPS training. That’s exactly right, everything you said. Obviously, I came from an African-American community, so I rejected the whole idea. But when I was being trained as a CPS worker, you were conditioned.

JJ: Right. And we have to transform the culture of our institutions, to examine that kind of thinking when people come to work, and it needs to start early in the process, where we begin to talk about the history of the racial inequities, even the history of the child welfare system. I can’t tell you how many staff I’ve been in a room with, social workers who really don’t know that history … so, if all they know is that we have disproportionality—which any rational person would believe if certain groups are disproportionately represented in the system—then [those communities] must be abusing and neglecting their children at a greater rate. If that’s all you know, then that’s what you believe, right? So, we have to transform our culture to really begin to tell the truth about history, and if we don’t go back and reveal that history, then we keep operating out of those same old attitudes, assumptions and stereotypes. We have been socialized as helping professionals to develop programs and services to fix the people.

SM: From that pathological space.

JJ: Absolutely, and white people have actually been socialized to believe—and in most instances, it’s well-intended—that they have the answer to what needs to happen to fix nonwhite people—in particular, black people, right? What is broken is not the people, yet we keep developing programs to fix broken people and when they don’t work, we point at the people. So, my work is really about turning the mirror inward, becoming critical lovers of our systems and institutions, to love the work we have chosen to do so much that there are no pieces of it that we’re unwilling to examine and critically analyze to consider the brokenness of our systems and institutions. Because the bookends are still in place, and white is on top and black is on the bottom and other populations fluctuate somewhere in the middle, then we have to believe there is something inherently inferior about the people, but I think we ruled that out some time ago, right?

SM: Although it resurfaces.

JJ: Or we have to be willing to examine systems and institutions, right? I can tell you that when we did that at the state level in Texas, we had some unprecedented outcomes. For the first time, we had more youth leaving foster care than coming in. We tripled our kinship placements. We had a 45 percent increase in services to families in their own homes, and we had astronomical numbers in adoptions as evidenced by the adoption incentive awards from the federal government. Now, when the system got better for African-American and Native American children, it also had better results for white children, which is our ultimate goal, right? When the bar is raised at that level, it is raised for all.

SM: What I like that you said, is that we have to be trained to understand racial competence. How do we move from this whole idea that, “I went to the training, I got my certificate and now I know what to do”? But we’re not looking at data. We’re not holding ourselves accountable to anything. How do we shift this to even think about becoming racially competent?

JJ: Well, I think we can use the data to start the journey toward having systems look that way, because what the data will show us [is] all things equal. Race is the predictor, so if our cultural competency training and work is effective, then it should be impacting the data. And so, you have to have in place methods to measure and evaluate the impact of any of the training we’re doing. We have to evaluate those outcomes—again aggregated by race and ethnicity—but first, people have to be given a space to even talk about race and racism. How can we be culturally competent if we can’t even say the word “racism,” when we know race is the driver of all outcomes?

This morning, when I was raising the issue about institutional and structural racism, afterward a couple of people came up and said, “You know people still are not comfortable with that language.” We know cultural competency is not enough because it doesn’t go to the source of the problem. What it does is help us to maybe understand why something might have happened to a person, and then we treat the symptoms. We still place the burden on the individual for why something went wrong, and so, getting into race competency means we have to create a space to just speak the language. We have to have a knowledge and understanding about how institutional and structural racism looks and how it lives and breathes in the spaces and places where we work, right?

For example, when we could look at our data in our child welfare system in Texas and recognize that when we did a deeper analysis, that families come in for the same or similar allegations of abuse and neglect, and we use factors like poverty and single parent households … we were more likely to provide in-home services to white families in the exact same situation where we were removing African-American children. Getting into race competency means that we have to be willing to do that deeper analysis. We have to have an understanding of how we’ve been socialized around race that leads us—and when I say us, I mean across racial lines, because we have all been socialize in the same way—nonwhite people toward inferiority and white people toward superiority, and it creates what I call a double-whammy, because we act out our internalized racism on the same populations of people.

SM: Another thing I love about what you’re saying is that—and you keep on using it—this whole notion of “journey” and so when I think about “journey,” it is from one place to another place … a nation of new ideas and strategies. It’s just sort of having some “a-ha!” moments. So, every space along that journey you’re learning. You’re enveloping ideas. When I think about it, we’re becoming a more mature space. What I also understand is that you have to be committed to the journey, and so you started this work a long time ago, and you’re still committed to the journey. Can you talk to us about this whole notion of the child welfare system at the start? You know, we stopped, we start and we stopped. I don’t see this idea of journey. I see it as, it’s been a training and we think we know or something happens and we get another project, so how do we create this journey, regardless of who the director is, so when this director leaves, the journey is still happening in the system?

JJ: One of the most challenging things about staying on the journey in child welfare is the nature of the work and how child welfare leaders don’t stay a long time. It’s also very important recognizing that for that work to even begin the journey, we have to have leaders who are willing to take the risk associated with it, even using the language. This morning, I applauded Allegheny County because they knew when they invited me, the language that I would use, because I refused to use any other language other than “institutional and structural racism,” because we have to be willing to call it what it is, and so the journey will be successful or not depending on who the leadership is until we are able to develop cultural change that lives and breathes in the fabric of the institution such that it does not matter who is in charge.

Right now, I don’t know of anywhere in a child welfare system across the country where this work has been able to be sustained over a long period of time. Even in my experiences with the work in Texas, people say, “Well, you know, what can we do to go back to our system and get people to work?” And I say, “Well, I was in a unique position because I was the leader, and it’s not always the people who are in the top-level positions who are the ones saying, ‘let’s make a commitment to do this work.’” One of the challenges that we have to deal with, those of us who have been in this work and maybe are involved in some work like BACW [Black Administrators in Child Welfare] is to say, “How do we support leaders who are at the top?” Because that’s how all the other people get the OK to talk about this work in a real and genuine way and use language that is bold and courageous, and so there has to be a willingness to take the risk that’s associated with doing this work.

As leaders, we have to make the decision to start removing the pressure from the institutional box to conform to the institution. That’s a space where a lot of child welfare leaders are today. The institutional box they have been put in has been designed so tight and to be so resistant to change that people don’t have the skills, nor the capacity, to organize to push against those walls. We pushed against the institutional wall for a long time and they gave. When they gave, we saw all of the amazing changes in outcomes for children, youth and families.

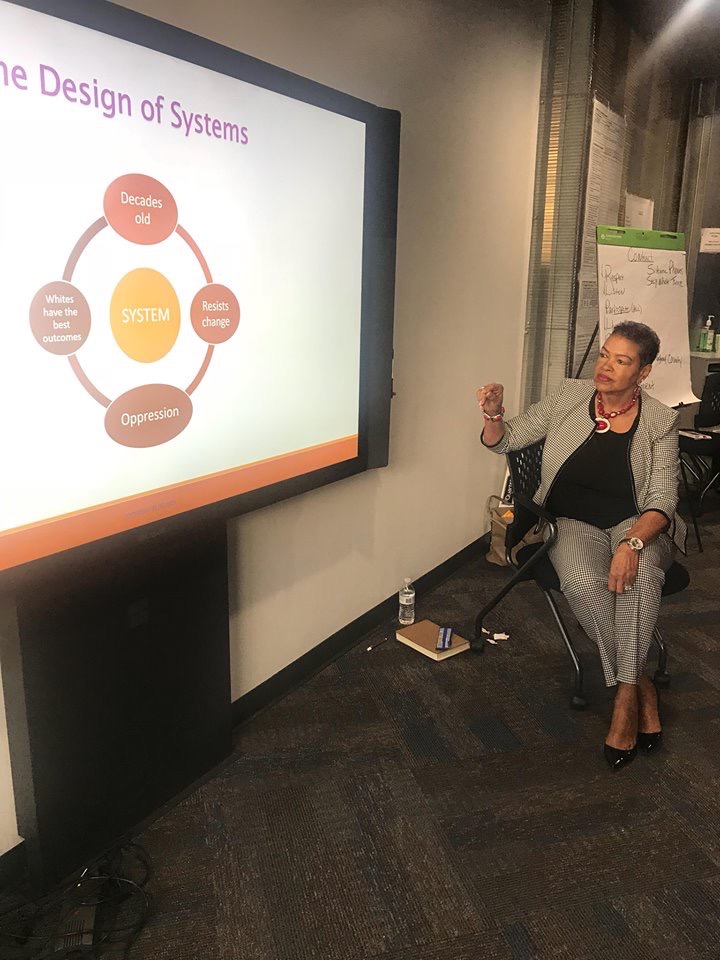

As soon as we started to let up, the institution began to revert back to the old way of doing business. That’s the nature and design of systems and institutions. They were designed to exclusively serve and benefit privileged white people, and the evidence that they’re still doing that is in the bookends. We know that we have worked cross-racially to push against those walls, but they have been so powerfully designed that it takes being intentional and deliberate, and recognizing that there is “no quick fix” to hundreds of years of oppression and racism. Right now, in Texas and a lot of other places, is that when we let up, systems revert back to their old way of doing business. Right now, in Texas and a lot of other places, we just keep trying to reinvent the wheel. We keep starting the journey all over again while children, youth and families continue to suffer, because we don’t have a culture that supports good outcomes for all of the children, youth and families that we touch.

SM: We were talking earlier about what you were doing at the individual micro level. I remember this one day, I placed all 10 siblings, they all stayed together. So, I was pushing against the system, like you said, individually. To go back to say, you’re 20-something-year-old self in the system, what would you tell the worker who doesn’t have a voice? Because what I think you taught me, was about dealing with my own internalized racial oppression. What would you tell your 23-year-old self now that you’re on this journey and you have a voice?

JJ: I do constantly look back at the lens I had then and the impact that had to shape my work going forward. I tell my story to people all the time … when I was a caseworker working my first job in a county that had, like, two large cities and court within one of those cities, I can remember the kind of thinking that said, if family didn’t show up in court, then they didn’t care about their children. I can remember not looking at the institutional and structural barriers like transportation, like time of court, like not being able to get off work, like losing your job because of how we set up things to accommodate us, like the conflict between, “I need to go and do the service or go and follow up on my service plan and lose my job,” and the other side of, “I have to have a job to get my kids back.”

So, we have to begin to have the time and analysis where we can have a new story. I have a lot of old stories about the damage I did when I didn’t have an analysis and understanding, because I was caught up in the sickness of internalized racial inferiority that caused me to somehow let the system tell me that I was different than the people I was working with and that they weren’t like me because they didn’t try hard enough … they just liked living in the situations they were in, liked being poor living on government assistance … but when I began to examine systems and how they exclude, exploit, oppress and underserve the same people and the collective impact of all of those institutions on the same people. I got that analysis from People’s Institute and I lift that up in my work, and the workshop that I do and the framework that I use is based on their anti-racist principles. And what I say to my white colleagues is, “You have to be anti-racist. You have to first acknowledge that you do have superiority in your relationship with systems. You didn’t ask for it and you can’t give it away, because it’s inherent in the design of our systems and institutions.” It was set up to be that way.

And the pain that communities experience … if we can get in touch with that pain and that community loss, as one of my friends from New York did a whole study on community loss, so you can look at certain communities down to the ZIP code level and know the loss that that community experiences from having their children removed disproportionately, having schools fail their children, having young men in juvenile lock-up, having their adult males in the criminal justice system, having black women disproportionately die after giving birth, having black babies disproportionately die during their first year of birth, having a lower life expectancy—and to have to deal with that in a space where systems come in every day in the name of help, and when you don’t see that help in the data, they place the burden and the blame on the people.

My journey … I’m still on it, I know that this journey has to continue. I hope that those of us who are still in the struggle can somehow create a space where people don’t have to continue to start over on the journey. People say, “Joyce James, you’ve been working for all these years, when are you going stop?” I know the difference that this work can make when we do it. Somebody may come behind me and dismantle it, but it doesn’t take away what it did when it was happening.

SM: We hide behind the term “cultural competency” in the child welfare space, even in the educational space. I’m just wondering, what is your approach in really changing a group of white people as opposed to changing one person. Because we’ll always be able to change the caseworker or director, but how do you change that group?

JJ: Well, you know, my approach is that it’s not one caseworker at a time. The way you change how people act inside of an institution is you change the institutional culture. What happens right now is that institutions put the accountability on individuals, but they don’t have anything in place to really measure or monitor whether or not individuals are actually becoming culturally competent. So, when the institution creates a culture that supports people in the development of their racial-equity lens and a greater consciousness around race and racism and how it lives in our institutions, then the people who don’t work in that way will stand out. In the absence of such a culture, institutions place the blame on individuals without any institutional accountability.

Let me just give you one quick example that I use all the time with child welfare. So, there was even something in the newspaper recently about CPS caseworkers being fired for falsification of their documentation. I’m not excusing that, but what is it about the culture of child welfare that might promote that? So, whether you have a manageable caseload or not, you still have to make your visits, right? And if you don’t, you’re not in compliance. And so, we fire caseworkers, but we don’t change the culture of the institution, so it just continues to happen. The same thing is true with race competency. Someone makes a bad judgment or decision about race, they get blamed for it, but nothing changes about the culture, so individual behaviors continue and institutions use the “bad apple” response of getting rid of one person at a time with no accountability for the culture that allows it to continue.

SM: That’s a really good example. I think we have that here, because I really try to look at when I stayed in my establishment. I’ll take the hit on the DPW compliance side. What I won’t take the hit on is that you’re not seeing the family right and seeing what they need. So, you make a choice to make sure you’re getting what they need. I don’t deal with the department side saying, “listen, they can only do what they can do” with all these unfunded mandates and paperwork. Are you more concerned about that or the families and children receiving what they need?

JJ: You have to create a culture that defines for its members how they will act in their relationships with everyone.

Joyce James began her professional career as a Child Protective Services (CPS) caseworker. She has established an impressive 39-year history in leading and supporting efforts for addressing institutional and structural racism in systems. She has a powerful story of her journey from CPS caseworker to Assistant Commissioner of Texas CPS, to Associate Deputy Executive Commissioner of the Center for Elimination of Disproportionality and Disparities (CEDD) and the Texas State Office of Minority Health, at the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, serving in that capacity from September 2010 to October 2013.

CEDD was created by HHSC Executive Commissioner Tom Suehs out of recognition of Ms. James’ strong and effective leadership and his desire to expand the Texas Model for Addressing Disproportionality and Disparities (Texas Model) to all HHS agencies and programs.

Ms. James, through Joyce James Consulting (JJC), provides technical assistance, support, training and leadership development to multiple systems, institutions, and community-based organizations across the country. She is the 2016 recipient of Texans Care for Children Founders Award in recognition of her “fearless leadership and fierce commitment” to children in Texas. She received an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letter in May 2017 from University of Saint Joseph’s in Hartford, Connecticut.

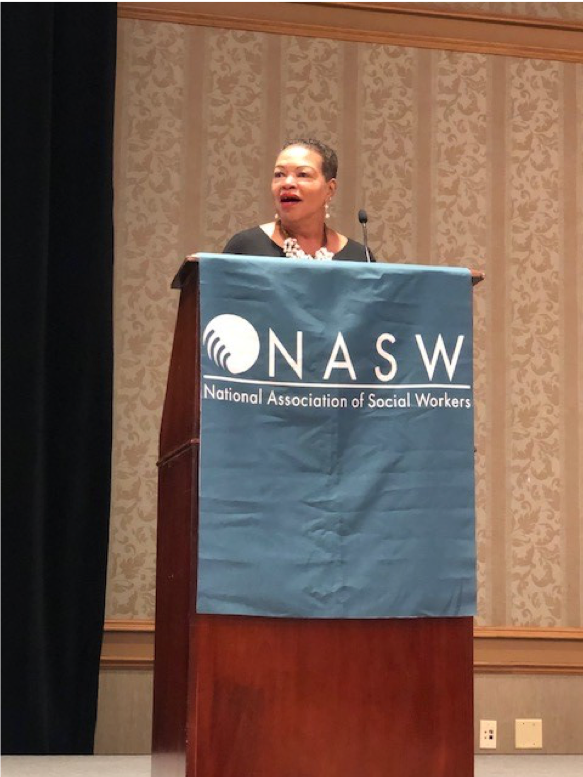

She is also the 2019 recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award presented by the National Association of Social Workers, Texas Chapter.