Blog

Vulnerable Youth Are Stuck in Traffic We Can’t See

The covert yet persistent human trafficking industry prays disproportionately on homeless foster youth, but the fundamental benefits of kinship care can serve as protection.

On average, within a 12-month period, one in 10 young adults (18-25 years old) and one in 30 youth (13-17 years old) experience homelessness, according to researchers at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, representing approximately 4.2 million young Americans. They further note that “that nearly one-third of youth experiencing homelessness had experiences with foster care.”

Covenant House reports that 68% of youth who are either trafficked or engaged in survival sex or commercial sex do so while homeless. The direct correlation between homeless youth and human trafficking comes as a result of the “low risk” such youth present to traffickers; they are already unprotected and vulnerable, thus, easy to manipulate.

Covenant House Associate Executive Director Hugh Organ explains that while anyone may be at risk of becoming a human-trafficking victim, there are populations of youth who may be more vulnerable than others. “Kids who are runaways are at a great risk of being trafficked. Kids who are in the child welfare system are at a great risk of being trafficked. But really, we’re talking about kids who are under the age of 18,” he says. “Traffickers are preying on kids as young as 12 and 13 years of age, which is a very difficult time for kids because many are just entering puberty, they may begin bumping heads with their families or they’re not comfortable with their bodies. And traffickers know this and use this to prey on these kids.”

Continual exposure of this longstanding, worldwide issue is crucial, as many youth are suffering in plain sight. “There are no real statistics to show how many kids are being trafficked—or specifically in Philadelphia—because the whole idea of trafficking is not to be noticed and is done under the radar,” Organ explains. “So, there’s no real way to know how many kids are being trafficked, but worldwide, they estimate that there are over a half-million victims a year.”

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) explains that cases of human trafficking have been reported in all 50 U.S. states, as anyone can be trafficked regardless of race, class, education, gender, age or citizenship when forcefully coerced or enticed by false promises.

Despite this jarring fact, Organ explains that children in the child welfare system are at greater risk of becoming victims of trafficking, as they can experience unique vulnerabilities and have unmet fundamental needs as a result of being in care.

The Work to Unmask Human Trafficking, Support Victims & Protect Vulnerable Youth

Covenant House provides housing and supportive services to youth facing homelessness in 31 cities across six countries. Since 1999, Covenant House Pennsylvania (CHPA) has been a safe haven for youth in Philadelphia and York, Pennsylvania, who have experienced homelessness as a result of traumatic life occurrences. Serving more than 3,200 youth annually, the CHPA shelter and program provide physical, psychological and emotional support to positively transform their lives.

Dedicated to advocacy and research, Covenant House seeks to ensure youth are given opportunities to thrive by highlighting the varying factors that cause homelessness while simultaneously trying to mitigate the issue. Organizations such as CHPA are especially significant for youth experiencing homelessness, as this detrimental situation can lead to even more traumatic experience—such as human trafficking, which the U.S. Department of Homeland Security explains, “involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.” Because they are such a vulnerable population, youth experiencing homelessness are a target of the dark industry that is modern-day slavery, which profits more than $150 billion off victims worldwide.

“Traffickers promise that they can fulfill whatever needs you have in your life,” Organ continues. “And by the time [youth] realize it, it’s too late. Traffickers sell love. And that’s what a lot of these kids are missing. Especially kids in the child welfare system who have been neglected, whose families may not be engaged, or they’re dealing with their own drug and alcohol issues. Whatever it may be.”

Policy analyst at the Center for the Study of Social Policy, FosterClub board member and former ASCI Child and Family Services Assistant Director and Clinical Coordinator Nico’Lee Biddle, LCSW, offers some emotional and psychological impacts of human trafficking on youth: “Child trafficking—whether sexual, labor or other forms—can disrupt a young person’s emotional well-being,” she explains.

“Though specific mental-health research is still needed, there have been studies done to begin identifying some of the effects so that effective treatments can be developed,” Biddle continues. “The most common mental-health diagnoses found among youth who experience trafficking are post-traumatic stress disorder and various types of depressive and anxious disorders. The symptoms of these diagnoses can manifest in multiple ways: running away, severe reactions to touch or loud noises, attachment issues, food hoarding or other disordered eating patterns, anxious behaviors and mood fluctuations. Young people who have experienced trafficking may also be reluctant to trust others, and may struggle to maintain genuine relationships.”

Caregivers and caseworkers should be observant of these behaviors, in addition to a child coming home late, running away or staying away for more than 30 days at a time, and a child possessing hotel keys—all of which Organ explains should be red flags.

Further, the growing use of technology has made youth increasingly susceptible to the traps set by traffickers, Organ explains. “The new ‘street corner’ or the new way traffickers recruit kids is the internet,” he says. “Kids are playing these games online and think they’re talking to other gamers, [but] they’re really talking to traffickers. I tell parents to be involved in what your kids are involved in, because traffickers are there.”

The dynamics among trafficked youth in child welfare further impacts service delivery for caseworkers in kinship care, as Biddle explains it can “disrupt a person’s interpersonal development” (i.e., the way a person understands their place in the world and how relationships with others work).

“Because the field of child welfare often has high staff turnover, young people are almost constantly being asked to meet and trust new people to help them make sense of their lives while in care,” she adds. “Often, they are asked to ride in vehicles with people they have just met. It is important to remember that most traffickers know their victims and are not strangers—when a young person experiences a close friend or family member who exploits them, it may force them to learn that the world is not safe and that no one can be trusted” (i.e., “If my family would harm me, how can I trust anyone else?”).

Placing children in kinship care can help combat this distrust, as youth will already have an established connection with the relatives or fictive kin with whom they are placed.

Additionally, while children in care may be more susceptible to becoming victims, research suggests that youth with positive role models may be less likely to be trafficked—another advantage found when utilizing kinship care placements.

“We did a study [of nine cities] here at Covenant House, and what we found was that the No. 1 thing to prevent human trafficking was a positive, engaging adult role model who was actively engaged in a kid’s life,” Organ shares. “If you have kids who have parents or individuals and adults who are engaged and paying attention to [them] on a regular basis, then there’s a good chance they won’t end up being trafficked.”

Trauma-Informed Response

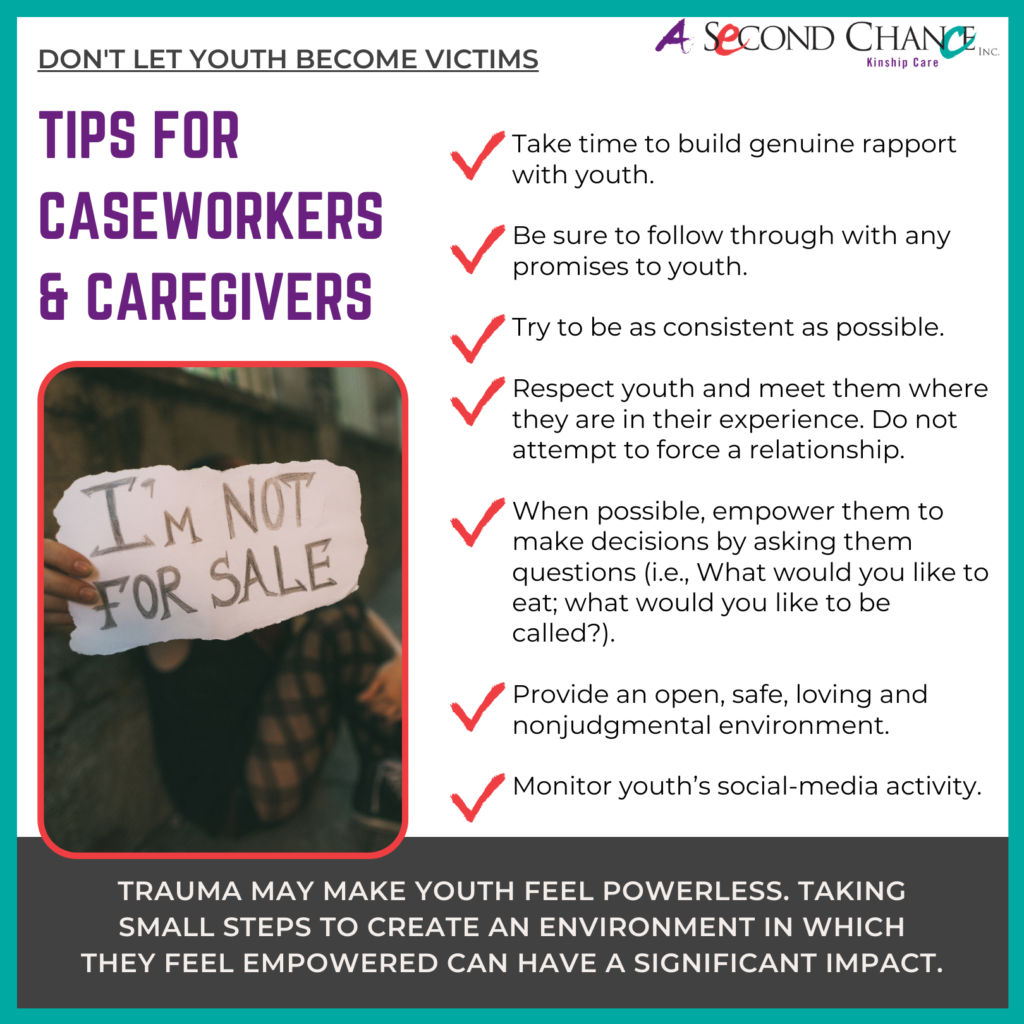

Biddle and Organ both stress the importance of caseworkers building genuine relationships and providing safe spaces for trafficked youth to feel empowered to make decisions, which may lead them to be freed from a trafficking situation.

Biddle clarifies: “The best way to combat resistance to service delivery is to take time to build genuine rapport with the young person, and to meet them where they are in their journey. For professionals, one of the most important things to remember is that a young person rarely means actions to be personal, and therefore if a caseworker feels rejected by the youth on their caseload, they should not take it personally and should continue trying to engage [them] appropriately.”

It is essential that anyone who comes into contact with a child victimized through human trafficking remembers that the trauma experienced may make them feel powerless. As such, taking small steps to create an environment in which that child feels empowered can have a significant impact.

“You have to be there for these kids and understand that their way of coping or dealing with this trauma is not ‘normal,’” Organ says. “But the conversation has to be about empowering this young person, and it starts with little things.”

The responsibility to help end human trafficking falls on all of us. As child welfare practitioners, parents, caregivers and members of society at large, we must take the necessary steps to consistently expose and share information within one another and our communities about this dark industry, which plagues so many of our youth.

As an agency dedicated to the safety and well-being of children, ASCI values the work of CHPA and other organizations that work to support and advocate for the indefinite number of trafficking victims across Pennsylvania, the U.S. and the world.

If you or someone you know is a victim of human trafficking, or you suspect it, call the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 for immediate assistance. You can reach the Hotline 24 hours a day, seven days a week in more than 200 languages. All calls are confidential and answered live by highly trained Anti-Trafficking Hotline Advocates.

Additional resources and information:

- National Human Trafficking Hotline

- National Criminal Justice Reference Service

- Covenant House PA Resources

- UNICEF

- The Department of Homeland Security Blue Campaign

- Polaris Project: Human Trafficking Myths, Facts and Statistics