Blog

Lessons from American Indian and Alaska Native Culture to Reorient the Child Welfare System

The forceful imposition of Western ideologies, practices and beliefs on indigenous communities have historically stripped them from their families, communities and culture. This heinous, historical practice of separation has been deeply embedded in the American child welfare system and continues to deprive Native communities of their family rights and connection to their culture. In this series, we engage in critical conversations with Dr. Sarah Kastelic (Alutiiq), Executive Director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA), to highlight the struggles of American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) tribal communities, and what we can learn from these very communities to reorient the child welfare system.

Installment II with Dr. Sarah Kastelic, Executive Director at NICWA

Protecting the Indian Child Welfare Act

Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in 1978 as a result of public and private state agencies removing Native children from their homes at increasingly high numbers. According to NICWA, “ICWA sets federal requirements that apply to state child custody proceedings involving an Indian child who is a member of or eligible for membership in a federally recognized tribe.” Added protections to the legislation require caseworkers to make a number of considerations when managing an ICWA case, and the following four primary placement preferences must be utilized when considering placement for AI/AN children in care:

1. Member of child’s extended family

2. Foster home specified by Indian child’s tribe

3. Indian foster home approved by an authorized non-Indian agency

4. An institution for children approved by an Indian tribe

Dr. Kastelic explains, “ICWA accounts for the best interest of kids by thinking about how we keep kids connected to their family, community and culture. One of the requirements for ICWA is the four preferences. So, when a child needs to be removed from their family, we can think about this hierarchy of where they should be placed.”

ICWA also gives tribal leaders a voice in ensuring children are placed appropriately to help maintain their sense of identify and culture—which is prevalent in their extended family communities.

“One important thing to point out about ICWA is there’s often a misunderstanding that when we say ‘extended family’ we only mean their Indian family. That’s actually not what ICWA says,” Dr. Kastelic explains. “ICWA says that if a child cannot be in their own home, the first preference is for them to be placed with family. Any family. That’s the most important thing is to have that continuity with family.”

The policies in place as set by ICWA have given the legislation the recognition of a “gold standard” practice for child welfare, as the emphasis on kinship and keeping children connected to their cultures and communities proves to have positive long-term implications for these youth into adulthood. NICWA’s continued research has highlighted the benefits of ICWA placements using kinship care, while some studies have also supported the positive outcomes kinship placements with extended family have for AI/AN youth, including the long-term mental health and well-being youth experience as a result of remaining connected to their cultures.

While ICWA was established to help ensure AI/AN children in care can remain connected to their indigenous heritage, many ICWA opposers have tried to insinuate that ICWA is unconstitutional because of race-related issues, and many states struggle to maintain compliance under ICWA as it has no official federal oversight to hold them accountable.

“There’s not good data. ICWA is the only federal child welfare law that doesn’t require specific data elements to be collected and for which there is no periodic review,” Dr. Kastelic states. “Every other federal child welfare law has some kind of review of data. How’s this impacting the outcomes of kids and families? What do we know about these practices? ICWA has no such thing. There’s actually no sanctions for not following the law. There’s no way that states can be punished for not following the law. There’s nothing in the law itself. In 2016, when the first-ever regulations were published for the law, finally there’s a way for tribes and individuals to try to be able to sue states, but litigation is a costly and lengthy process. Ultimately, there isn’t any sanction other than a particular custody matter has to be revisited. They have to start the process all over again if the provisions of ICWA weren’t followed, when in fact it was a case including a native child. This tremendously lengthens the process for kids and families, doing more harm, more damage while they’re involved in the system. So, that lack of data is a big problem.”

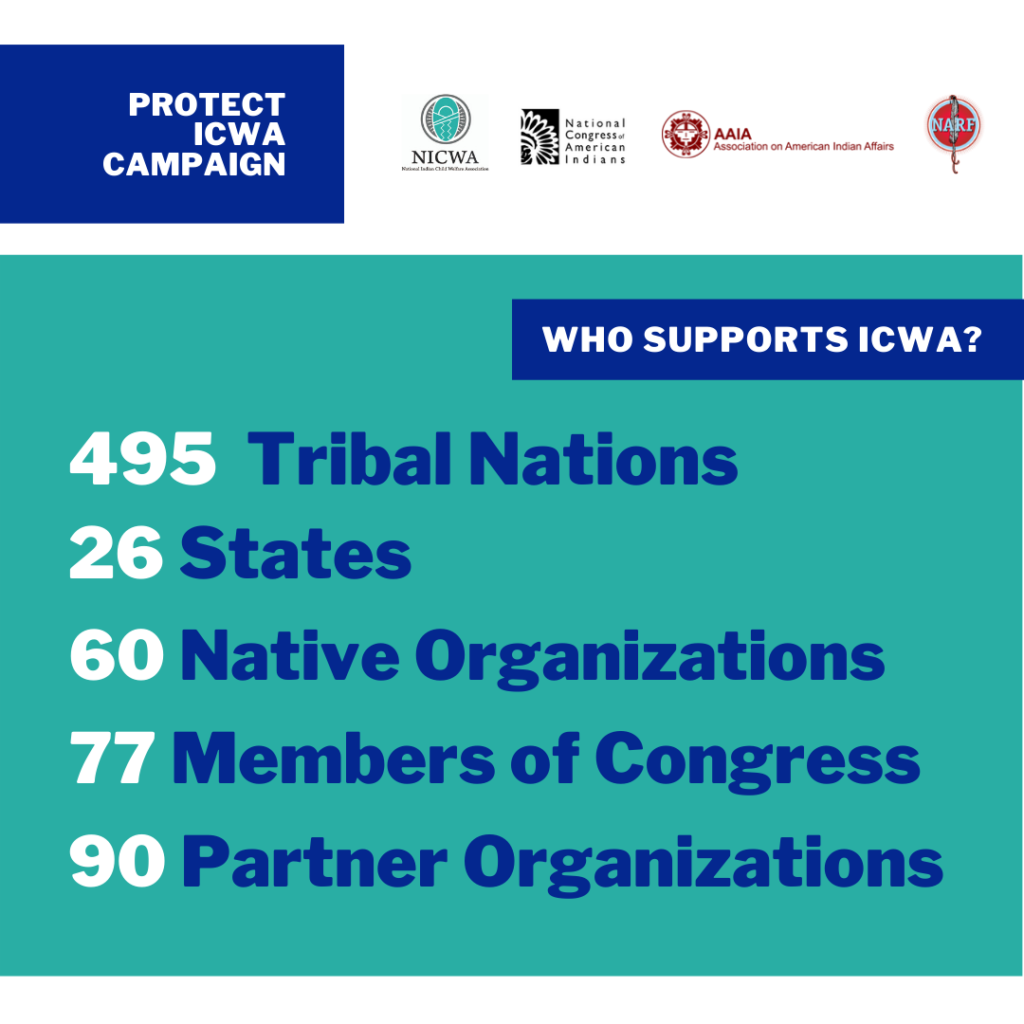

As such, NICWA, the National Congress of American Indians, the Association on American Indian Affairs, and the Native American Rights Fund established the Protect ICWA Campaign to “inform policy, legal, and communications strategies with the mission to uphold and protect ICWA.” Currently, the Protect ICWA Campaign is working to affirm the constitutionality of ICWA through court proceedings of Brackeen v. Bernhardt, the lawsuit brought by Texas, Indiana, Louisiana, and individual plaintiffs in 2017, who allege the Indian Child Welfare Act is unconstitutional—the first time that a state has sued the federal government over ICWA’s constitutionality claiming it’s a race-based law.

Dr. Kasetlic explains, “The case was appealed to the fifth circuit court of appeals where it was heard by a three-judge panel, and they found ICWA to be constitutional. But, there was a dissent around one issue, which had to do with some of the requirements of ICWA. But because there was that small dissent, the opposition—the states of Texas, Indiana and Louisiana, and a handful for non-Native foster parents wanting to adopt Native children—requested an en banc rehearing of the case, which means they’re asking all 17 judges to hear the case again at the same time. That happened earlier this year in January, and there isn’t any deadline for the court to hand down their decision. So, we’re just kind of waiting now to see what happens.”

NICWA’s Protect ICWA Campaign has become a critical aspect of their work. Opposition of such cases like Brackeen v. Bernhardt creates greater uncertainty for hundreds of AI/AN families and children who are currently navigating through the child welfare system. For Dr. Kastelic, this campaign is also important because she witnesses first-hand the challenges many face as a result of not knowing the law and navigating the child welfare system without assistance.

“The vast majority of the calls we get unsurprisingly are from families,” she says. “They’re either families that are struggling to navigate the child welfare system and trying to figure out what protections apply to their family, or, another major group of calls we get are from adult adoptees. They are from people who were adopted out from their tribe or family and they’re trying to find their way back home, they’re trying to find where they belong. And, those are some really challenging calls to take.

“I hear on a weekly basis from people who are suffering because of that severed relationship with their family, community and culture. I talk on a weekly basis with people who are saying, ‘I don’t know who I am, I don’t feel like I fit anywhere,’ and that has devastating consequences for their well-being. So, ICWA is so important to me because I see the damage that is done to those children and to their families when they’re not able to maintain that relationship.”

“I hear on a weekly basis from people who are suffering because of that severed relationship with their family, community and culture. I talk on a weekly basis with people who are saying, ‘I don’t know who I am, I don’t feel like I fit anywhere,’ and that has devastating consequences for their well-being. So, ICWA is so important to me because I see the damage that is done to those children and to their families when they’re not able to maintain that relationship.”

Reorienting the child welfare system to be more inclusive of diverse cultures must begin with dismantling the historical, one-dimensional context of who family should be. Thus, by unlearning these standards and seeking knowledge about these differences, we can begin to shift our societal ways of thinking about family and permanency for children, toward a more empathetic attitude about parenting. By emphasizing that raising children requires the love and support of the community, we can begin to break down the systemic barriers that have continued to place children and families of color at a disadvantage in America.

Dr. Kastelic explains, “When you reorient the child welfare system in a way that’s really about recognizing the humanity of families, recognizing that parenting is hard, recognizing that we all need support and help with parenting sometimes, that that’s just the norm, and then providing a space for those things to happen, then we don’t ever have to get to the point where there are bruises or abandonment. Or, at least it’s happening far less regularly because people are stepping in long before then.”

For more information about how to take action to support the Indian Child Welfare Act, visit NICWA’s website.