Blog

Toxic Stress in Children: What It Does and How to Mitigate It

Feeling stressed has become a more frequent expression as we are challenged more every day by the impact and implications of COVID-19. Stress is always present in our lives, and in small doses we know that it does have some benefits. It can be an adrenalin booster that provides energy and refines focus. For example, think about a time when the stress of a deadline contributed to an outstanding final outcome.

We also know that stress can never be totally eliminated. It is impractical to think that way. We learn how to manage stress as part of daily life; however, instances exist where stress becomes serious and impacts our mental, emotional and physical health. In children, this impact is heightened.

If a child lacks a supportive environment during times of adversity, they may never learn ways to cope with stressful situations. Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child describes toxic stress as the “excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and brain,” which can negatively impact healthy development in children and have lasting effects on their learning and behavior. As research suggests, this unrelenting stress can increase the likelihood of developmental delays and health problems in adulthood, including heart disease, diabetes, substance abuse and depression.

Researchers at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall are examining some of the innovations employed by pediatric primary care clinics in coordination with community-based programs to better prevent and mitigate toxic stress among families receiving pediatric health care. Included in Chapin Hall’s research is an analysis of family experiences of health care and toxic stress.

“Toxic stress really refers to a physical reaction to stress, and that stress is ongoing and unremitted,” explains senior researcher Julie McCrae, whose professional experience focuses on health and development in children who are exposed to toxic stress, primarily originating in the relationship between parents and children, and family relationships. “We’ve all experienced stress and we know what happens in our own bodies. Our heart rate quickens. We may feel some sweating in our palms. We may feel lightheaded. When the stress you would have in an acute situation—like being exposed to a bear or almost being in a car accident—produces that response on an ongoing basis, and there’s not something to take that away or decrease it and let your body return to normal … that can result in your body really adapting to that stress and making actual physiological changes that can be impactful over the long term.”

“There are structural sources of stress for a lot of people,” McCrae continues. “So, the way that your neighborhood is … to where you feel unsafe going outside; poverty, not having enough food and worrying about where that’s going to come from … some of these issues are really structural and woven throughout society.”

Chapin Hall research fellow Amy Dworsky adds, “Sources of stress can be varied. It can be stressors that are in your family, in your neighborhood. When we think about stress, we think about it broadly.” Dworsky’s work is mainly divided between child welfare and youth homelessness and in the child welfare space.

McCrae continues, “Not all stress is negative … and it’s never too late to address stress in terms of buffering that response. What I mean by that is children are really depending on caregivers to provide safety and healthy communication and structure, and that’s been found to be one of the most promoted factors in terms of how children respond to stress and reducing the impact of chronic stress.”

Children in care are faced with a unique source of ongoing stress—being separated from their parents. This may be heightened for some, as there are a number of factors they must navigate when trying to maintain a relationship with their birth families. Thus, it is important for caregivers to provide supportive and healthy relationships to address their responses to these factors as soon as possible.

However, toxic stress can be caused by a myriad of factors and materializes in a myriad of ways. “I think there’s all sorts of signs you can see in a child: behavior problems, signs of depression or anxiety … but being taken away from your parents and put in someone else’s home could just as easily cause those same reactions.” Dworsky explains. “Saying that’s due to toxic stress is an issue. I’m not sure that we could make that conclusion at this point. ” Due to its ambiguous nature, the logical focus should be on preventing stress from becoming toxic in the first place.

For families, this means incorporating healthy coping strategies into the home and providing love, security and support to promote resiliency. But what does it mean for child welfare agencies? Are we training kinship caregivers on healthy stress relief strategies and how to integrate them into their parenting techniques? Are we asking enough questions about mental and emotional wellness during home visits? Are we providing clinical resources? As more is discovered about toxic stress and its harmful short-term and long-term effects in children, child welfare as a sector must be paying attention to ensure everything that can be done will be done to prevent toxic stress from hindering children and families’ well-being.

McCrae emphasizes that while toxic stress is a process that can develop as a result of unresolved physical reactions to stress, it’s never too late to address it in order to mitigate it moving forward. “Let’s be clear that it’s never too late to practice good responses to stress,” she states. “It’s never too late to have healthy communication with people and provide healthy relationships, and really focus on resiliency and present it in a way that there’s hope.”

In maintaining this hope, ASCI values the work of Chapin Hall in addressing how our systematic role in mitigating toxic stress – especially in times like this – can ensure our children and families have the best opportunity to thrive.

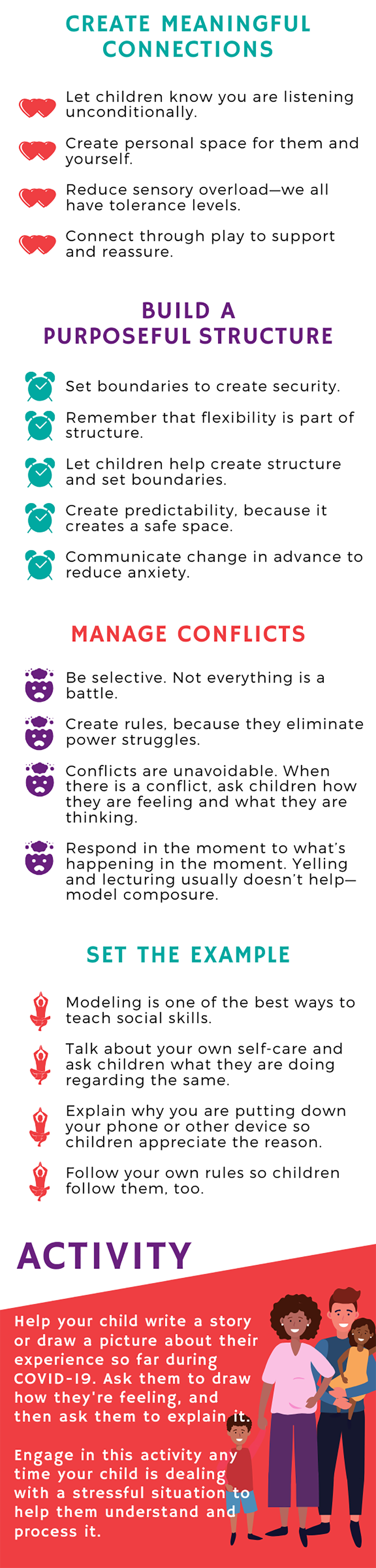

ASCI Child and Family Services clinical coordinator and supervisor Nico’Lee Biddle, LCSW, provides helpful tips that kinship caregivers and parents can use to help prevent toxic stress in children. It is crucial to remember that children learn by example. It is no secret that becoming a kinship caregiver is typically unexpected and can create stress.

Dworsky explains, “I think we know from the child welfare literature that kinship caregivers are frequently themselves under a lot of burden. Economic burden; many of them are older and have health issues, which can make it difficult to be a caregiver … there are a number of issues to think about when you’re talking about kinship caregivers. Toxic stress or anything else, children can sense when something is wrong in the home. They are very intuitive.”

Providing a nurturing environment and practicing healthy stress relief techniques themselves will help caregivers and parents teach children to cope in healthy ways, as well.

Dr. Julie McCrae is Senior Researcher at Chapin Hall. McCrae specializes in interventions related to toxic stress exposure. She is Co-Investigator of Evaluating Community Approaches to Preventing or Mitigating Toxic Stress, a multisite, national study of innovations in health care to address toxic stress. McCrae leads the Support, Connect, and Nurture program (SCAN), which integrates social worker and parenting resources into pediatric primary care to strengthen supports to families to promote healthy child development.

McCrae was previously Research Associate Professor at the University of Denver, Graduate School of Social Work, where she led research and program evaluation in child welfare services and early childhood. McCrae is an experienced analyst, with over 15 years’ experience analyzing longitudinal data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW), a nationally representative study of children involved with child welfare services.

McCrae has a PhD in Social Work from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, an MSW from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Pennsylvania State University.

Dr. Amy Dworsky is a Research Fellow whose research focuses on vulnerable youth populations—including youth aging out of foster care, youth experiencing homelessness, and youth in foster care who are pregnant or parenting—and the systems with which those youth are involved. She is currently the Principal Investigator (PI) for an evaluation of a pilot program that connected pregnant and parenting youth in foster care with home visiting services and the Co-PI for a study that will inform the development of policies and practices that are responsive to the needs of incarcerated mothers in the Illinois Department of Corrections. Dworsky is also working with a team of researchers from the Urban Institute on a federally funded evaluation targeting programs for young people transitioning out of foster care and with Chicago’s Continuum of Care to improve the provision of services to young people experiencing homelessness.

Dworsky was a Coinvestigator for a longitudinal study of young people who aged out of foster care in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin and the PI for a federally funded study of housing programs for former foster youth. She conducted the first study of child welfare services involvement among children born to foster care youth and led the first evaluation of a pregnancy prevention and sexual health training for caseworkers and foster parents. Dworsky was also a Coinvestigator for Voices of Youth Count, a national research and policy initiative focused on ending youth homelessness, and worked on the development of an intervention strategy to improve the outcomes of foster youth at high risk of homelessness as part of federal planning grant.

Dworsky has experience using both quantitative and qualitative research methods, analyzing administrative data, and partnering with public and nonprofit agencies to conduct policy and practice relevant research. She has a PhD in Social Welfare from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a Master of Social Work from Syracuse University, and a Bachelor of Arts from Williams College.