Blog

30 Years of Knowledge Building for an Effective Kin-First Culture: A Natural Family Resource for Children in and out of the Child Welfare System

Sharon McDaniel, Ph.D., EdD, MPA

President and CEO, A Second Chance, Inc.

I am an alumnus of what is now known as kinship care. Today we prefer to call this “lived experience.” I want to tell you why that distinction is important.

Last week, the headlines of an article bandied about the child welfare sector, asking, “Can Kinship Care Help the Child Welfare System,” adding that the “White House Wants to Try.” As a lifelong kinship care advocate, let me first state that I am grateful for the recent attention kinship care has received. Since the early 1980s, I have been in these same conversations. From my initial role as a CPS caseworker, to founding my kinship agency, to sitting on the White House’s Adoption Safe Family Act Commission under President Clinton in the 1990s. The conversations are the same although they have new well-intentioned people sitting in these critical seats.

I would ask why the child welfare system has been stuck in these same conversations as a system for decades. The answer is that you cannot legislate or purchase morality. The value of kinship care as a system response has been absent in child welfare as a system!

In 2000, there was a divestment in kinship care, as the federal government issued the Final Rule that precluded states from drawing down IVE for any unlicensed kinship family during the certification period. Before the Final Rule, states received federal support for kinship families when children were initially placed with kin. This immediately stopped preservice resources from going to families during the licensing period. Consequently, some states were unwilling to invest state dollars during this early licensing period. The proliferation of shadow foster care/ kinship diversion became more accepted among state and federal officials.

In the current environmental kinship care context, some system leaders and those in their orbit that have supported them have been and remain steeped in racist and classist ideology that suggests the “apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” Throwing 20 million dollars at a fractured system that has cared less about kinship families who have “helped and saved” the system for decades does not go far enough. While I will “extend grace” to the effort and the critical question and responses to the recent article, it does not answer why children are in the child welfare system in the first place. Foundationally, government intrusion in the lives of families must be critically explored; otherwise, it is the system with simply more money to continue business as usual.

What if the article read: “White House vows to address the structural and institutional racist and classist issues which bring children into care, and support kinship families if and when temporary out-of-home kinship care is needed.” What if they said, “The parent’s role is the leading critical role in the well-being of their children?” What would be the response? The latter is why A Second Chance, Inc. has “ALWAYS” supported the “Kinship Triad” of parents, children, and caregivers; our role is to ensure the family system remains intact, not further fracture it.

While I support the need for additional support for kinship caregivers in and outside the child welfare system, understanding the “what and how” is imperative. The article does not go far enough in articulating the differences between a child welfare system and a child well-being community response and support system. These are two different systems and attention to the constructs of such systems must be thoroughly explored and reimagined.

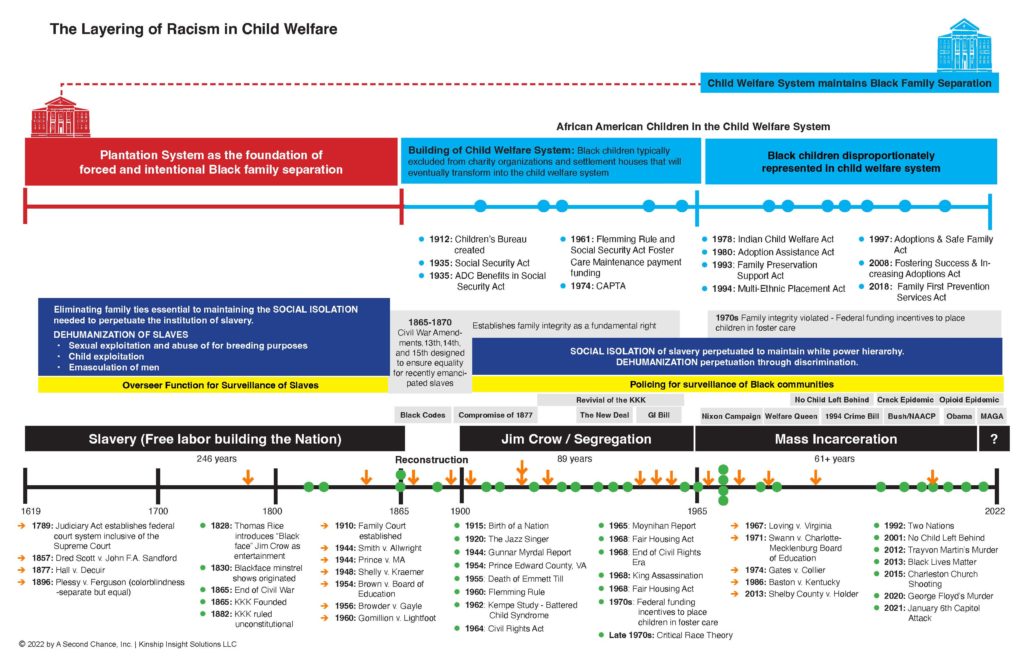

Today, I offer two thoughts: One, we need to examine how child welfare policy in this country has failed children, youth, families, and their communities for decades and Black families since 1619. The timeline below gives you, the reader, an outline of the failed policies impacting the poor, Black, and Brown families who have and are touching the child welfare system. Second, I will share what we have learned in our almost 30 years of providing direct support to kinship children, youth, families, and their communities. This is where lived experience surpasses romantic ideas and where the accurate experience of “rubber meets the road” matters.

I aim to examine how our past policy constructs, which have been based on pathology, patriarchy, white supremacy culture, racist and classist frameworks, and savior mentality, must be arrested. New ideas which center on parents, children, and their communities, must be top of mind in any policy development, construction, and advancement. Additionally, I want to share what we have learned over almost 30 years of supporting the Kinship Care Triad.

Kinship Care as a Lived Experience.

My lived experience with kinship care began when I lost my mother just months before my third birthday. My father attempted but was unable to raise us and, by the time I was 17 and graduating high school, I had spent time in a group home for girls and lived in nearly a half dozen homes with families who weren’t my own. Some who opened their doors to me were like strangers – chilly and uncaring; others were like family, knitting me into their lives and embracing me in the bosom of their rituals and kinship. With them, I had a chance to grow up healthy and whole. I know now that was the power of kinship care.

While I experienced challenges as a youth, I emerged from a life interrupted by death, disappointment, and indifference. These things could have, depleted me, but instead, they became the fuel for my life’s work and purpose. I did not “graduate” from foster care as an alumnus, meaning I could fail “foster care,” which I could not – the system failed me. Fortunately, my kinship care experience assisted me in surviving the system; it enabled me to move on. I lived through the occasion with a story to tell

I choose to live the experience of kinship care every day.

Experience in and of itself does not guarantee learning; reflecting on that experience, however, does. I have remembered kinship care for a long time.

For almost 30 years, A Second Chance, Inc. (ASCI) has become part of my “kinship everyday” world. ASCI is a kinship care agency that works to meet the unique needs of kinship care families and continues to be a pioneer of kinship care. Through the years, we have learned a lot. There have been collaborations with philanthropic organizations and the formation of kinship-specific programs and policies – partnerships with counties and states. We’ve worked grassroots with the community to keep families intact and children safe. For 10,950 days, we have acted as a broker of second chances for children and families as they interact with the child welfare system. The model and staff of ASCI have helped shape national policy that benefits caregivers and elevates kinship care. We’ve learned a lot.

Kinship care itself is a culture of learning.

At ASCI, we remain active learners of kinship care. The most important learning for us about kinship care has been social. We’ve learned in and among groups of children, youth, kinship caregivers, and birth parents. We’ve learned kinship care from our dedicated caseworkers, trainers, and supervisors. We have learned from our national work with state and country directors, commissioners, field workers, and administrators.

On any given day, there are nearly 424,000 children in foster care in the United States. In 2019, over 672,000 children spent time in U.S. foster care, the disproportionality of one-third of the population being children of color. Across the nation, 4% of all children – more than 2.6 million are in kinship care. There are overlapping classifications of kinship care. Informal care, where families make arrangements with or without legal recognition of a caregiver’s status. Kinship diversion, where children who have come to the attention of child welfare agencies end up living with a relative or close friend of the family. The third is licensed (or unlicensed kinship care), where kids live with relatives but remain in legal custody of the state.

With all these different experiences, we consistently hear different narratives, viewpoints, and perspectives on kinship care from others in our community, our state, and child welfare jurisdictions across the country. We hear the positive, negative, and indifferent. Some are based on experience, most on myth and belief. Some of the more consistent thoughts shared with us during our national work include the following:

- It would help if you didn’t have to pay family to care for their relatives.

- Kinship homes are inherently a safety risk.

- Kinship caregivers are typically noncompliant with licensing requests.

- The foster placement is more stable if you can’t find a family within 30 days.

- Diversion is better because it keeps children out of the system.

- Reaching permanency in kinship care is a challenge.

This is despite the learning we find in Kinship 101; children do better with family. The benefits are there and documented in years of data. Kinship care:

- A natural response to child welfare rather than a prescriptive enforcement

- Lessens trauma

- Advances children’s well-being

- Increases time to permanency

- Positively impacts behavioral and mental health outcomes

- Better facilitates sibling ties

- Provides a bridge for older youth

- Respects and preserve children’s cultural identity

- Respects and maintains community connections

- Acknowledges itself as a better response to racism in child welfare

Our numbers of ASCI support the learning of Kinship 101.

- Length of stay for children discharged to reunification

- National Average: 7.6 months

- ASCI Average: 6.91 months

- Length of stay for children released to adoption

- National Average: 29.4 months

- ASCI Average: 18.49 months

- Percentage subjected to substantiated/indicated maltreatment/abuse while in care

- National Average: .26%

- With ASCI, % of investigations 1%; .0001% substantiated; approx. 45,000 children serviced

- Percentage of foster youth who complete high school

- National Average: 58%

- ASCI Average: 95%

Kinship Care learners grow by challenging their thinking.

ASCI has been coordinating the kinship care process with the Allegheny County Department of Human Services’ Office of Children, Youth, and Families (CYF) for 29 years. In this public-private relationship, we have also been partners in learning. We have, with intent, formed a learning unit where we assist each other in acquiring and developing the skills and knowledge that will lead to better outcomes for kinship families.

Four years ago, when kin-first placements started to diminish, we collaborated with our funder to develop a Kinship Navigator (KN) program that was differentiated from solely being a resource and support service. ASCI’s kinship navigators support CYF from the onset of a case by identifying and clearing appropriate kinship options; determining kinship services for families during non-emergency and emergency cases; identifying kinship options for children/youth who are currently in congregate care; screening located relatives and kin to determine their availability and appropriateness to care for children in need of placements; and improving the stability of placements.

While the ultimate goal for a child who enters custody is to return home promptly and safely, this does not always happen. Having a caregiver who supports the goal of returning home – or who can provide a permanent home if reunification is not feasible – will increase a child’s stability.

ASCI’s learning relationship with the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work is another example of how consistent learning partners improve kinship work. We collaborate with the University on issues of social, community, and governmental concern for kinship families. The University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work was our research partner on our journey to make the Kinship Navigator evidence-based.

Notably, this work and collaboration have led to ASCI’s Kinship Caregiver Engagement and Support Program (Navigation Program) achieving status as a promising/researched and evidenced-based model by the California Evidenced-based Clearinghouse.

5 Important Kinship Lessons Learned

There is no recipe for kinship care; there are, however, strategies and techniques that advance the likelihood of success. It’s akin to making a cake; sure, you can cream the sugar with a cold stick of butter, but things will move faster, taste better, and work better in the recipe if you let that stick of butter come to room temperature.

Lesson 1: Children Want their Own Families.

All children seek emotional closeness and care of family. “No child in crisis ever asks to be placed with strangers.” This is the basis of kinship literacy. It is the foundation for everything else.

Lesson 2: The Kinship Triad Guides the Work

Kinship Care work must include the Kinship Triad (the child, birth parent, and caregiver). The triad exists as a construct in every family, whether or not they are involved with the child welfare system. The three roles are naturally and intimately linked. Outside influences impact the intrinsic and unique qualities of the Kinship Triad and, thus, deserve specific attention when the complexities of child welfare are added to the family’s network. ASCI’s triad concept is built on the belief that children have a moral right to be with family when possible.

Lesson 3: A Kinship Care Continuum

As suggested by Shadi Houshyar from the Center for the Study of Social Policy, kinship care is better understood as a continuum; the boundaries between informal, voluntary, and formal kinship care are fluid and often blurred as many caregivers move in and out of these groups. Kinship caregivers—whether they are involved with or unrelated to the foster care system—provide a vital service as a safety net for children when their parents are not able to care for them.”

The concept of a kinship care continuum is not a universal approach for most child welfare systems across the country. It is, however, the defining characteristic of ASCI’s practice model of kinship care.

A kinship care continuum is a system that provides a comprehensive range of family-based services to the entire kinship triad (the child, birth parent, and caregiver) so that care can evolve with the family over time. With the understanding that safety, well-being, and permanency may be most vulnerable during gaps in care, the kinship care continuum exists to ensure those gaps are filled with and by the family system, with ASCI serving as facilitators of the process.

Lesson 4: Care Management Before the Case Management

Care Management is centered on compassion, where that compassion for families is not optional but vital. Logistically, care management is the team-based, triad-centered coordination of family-based services within the context of healing. It means more extended conversations, appointments, calls, and texts. It means easy access to a caseworker and services. Care management must ungird case management where we fit in issues of compliance and staff accountability.

Lesson 5: : Racial and Cultural Competency as Two Distinct Areas

ASCI’s Kinship Care Continuum recognizes that the child welfare system is inherent to institutionalized racism. Without this understanding, the context of how we work for families is not natural or realistic. The ASCI Kinship Care Continuum addresses cultural and racial competency as two distinct areas that impact policy, practice, and family engagement differently because there are elements regarding racism that are unparalleled in cultural attentiveness and must be called out separately. This understanding is essential in understanding the importance of family integrity in kinship care.

The Greatest Lesson: Empathy and Experience

Empathy is needed in kinship care; it’s how we connect with families. Being empathetic with kinship families means recognizing that our personal experiences are identified as all families deal with crises. Empathy allows families to feel safe voicing their needs, concerns, and experiences. There can be no care management without compassion for families. Empathy does not devoid itself of empathy. Assistance, support, and understanding in good care management only result from an emotional interaction with families.

While empathy is essential, it never replaces lived experience. If you have not been through the child welfare system personally, your level of understanding is much different from ours. Those with lived experience have learned something firsthand that others have not. Where we paint kinship care in bold strokes, those with lived experience paint it in nuances of color, light, and shadow we could not see.

Experience is not how we learn; reflecting on those experiences is where authentic learning occurs. Research, study, and narrative provide a wealth of knowledge on kinship care. However, in the child welfare system, much of this kinship care knowledge is devoid of context, unconnected to experience, and isolated in the policy. It keeps the child welfare system stuck and unable to transform its kinship care practice. For those in child welfare, who experience kinship care in some form every day, not taking the time to reflect on the learning will have little impact on family engagement.

After almost 30 years of a kin-first culture, take a minute to reflect on kinship care and answer this question, “Is kinship care a placement or a place for the family?”

Thank you Dr. McDaniel! A very informing, thought provoking and passionate essay. I have much to reflect upon.

Dear, Julie.

Thank you for taking the time and opportunity to ponder and reflect. I am eternally grateful for the same.

Kind regards,

Sharon

I work for an organization in San Diego, CA that provides CASAs to children in the dependency system. I recently tried to have a conversation with out Chief Operations Manager and was promptly told that my use of the phrase “white privilege” makes people uncomfortable and is “off putting.” We are supposed to have a retreat tomorrow to discuss San Diego’s push toward Kinship Culture and I am wondering how I can once again try to have the discussion about not only white privilege, but about the savior mentality within our organization and the disproportionate number of black and brown families we serve.

Hi, Kate.

Let’s take another route with this topic and refer back to the post. Why is Kinship Care helpful to the Child Welfare System?

ASCI’s practices:

1. Children Want their Own Families

2. Kinship Care work must include the Kinship Triad (the child, birth parent, and caregiver)

3. A Kinship Care Continuum

4. Care Management Before the Case Management

5. Racial and Cultural Competency as Two Distinct Areas

Additionally, we often talk about how complex and intimidating the child welfare system is. Kinship can maintain the balance of the family; it integrates with the strength and self-determination of the family. Most importantly, Kinship care keeps the family connected. It grounds the family in place. Kinship care provides clarity in how to work with families.

When thinking of Kin-First share our findings on how children in care have already experienced the trauma of being removed from their homes and families. Placing them in the homes of relatives or fictive kin reduces the chance for further trauma, while at the same time maintains their connection to their communities and cultures.

I hope this helps, feel free to navigate through our website for more information on Kinship Care and Kin-First Culture.