Blog

The Journey of Bernice Hayes and the Power of Forgiveness

This May, as we recognize both Mental Health Awareness Month and National Foster Care Month, we honor the countless voices of those who are – and were – involved in the foster care system, and the often-invisible emotional toll that journey may carry. Bernice’s story, shared with raw honesty and quiet strength, is one of many.

From an early age, Bernice Hayes experienced the complex realities of foster care — love and loss, acceptance and rejection, nurturing and hurtful moments.

Bernice’s experience in the child welfare system isn’t just a story — it’s a testimony to endurance, faith, and survival through instability. Hers is a voice that represents the thousands of young people in foster care whose identities were shaped and reshaped by transitions, rules, punishments, and rare moments of kindness. It’s also a voice that echoes the long-term emotional toll of growing up in a system that often prioritizes placement over permanence, and compliance over care.

Bernice’s first foster home felt like the only home she truly knew — until the unexpected death of her foster mother. “They wouldn’t allow a man to foster alone in the 1950s, so we had to go,” she recalls. That sudden uprooting marked the beginning of five different placements, each with its own set of expectations and fragile attachments. Amid the constant movement, Bernice still remembers glimpses of love. Her first foster father made every effort to stay in touch. “He would visit, bring birthday gifts, Christmas presents etc. But they made him stop.” Her second foster home introduced harsh discipline and strict routines. Despite the cruelty, Bernice and her siblings found solace in being together — a closeness that was often paired with their need to survive, their behavior, or a foster parent’s decision to separate them. The deep bonds they shared were constantly tested by revolving doors.

The third home brought a different kind of tension — one rooted in religion. “We had to join their Baptist church and get baptized. We were raised Methodist. It wasn’t a huge jump, but it was just… different.” Once again, after just a year, they needed to move.

The fourth placement came with even more confusing rules, this time dictated by a faith she had never heard of before. “They called themselves Commandment Keepers,” she explains. “We couldn’t do anything on Saturdays. It was confusing.”

Eventually, her sister left the city to work — a separation that shook Bernice deeply. “It was significant because she always protected me.”

And yet, even amid pain, Bernice dared to imagine a different future. “I decided I wanted to be a nurse,” she said. She threw herself into her education, despite having taken the wrong classes for nursing school. Determined to catch up, she shifted to a more rigorous academic track and began to thrive. But when deadlines passed and applications fell through, Bernice made a choice that would change the course of her life. Her foster mother’s son-in-law was in the Air Force, and during a visit to a military base, something clicked. “I decided that’s what I’d do,” she said. “I signed up and left for basic training at 17.”

Enlisting in the Air Force wasn’t just about leaving foster care — it was about reclaiming control of her future. It gave her structure, identity, and most importantly, independence. At 18, while still in basic training, Bernice officially aged out of the foster care system. “I turned 18 in the Air Force — and that was that, no more foster care.” There was no party to mark her coming of age, just military drills and the sobering weight of adulthood. But for the first time, she wasn’t someone’s ward or case number. She was Airman Bernice Hayes — strong, self-reliant, and carving her own path.

Her military service offered stability that had been missing for so long. The Air Force gave her food, shelter, education, and the framework to grow — but hardship didn’t vanish. It traveled with her, tucked silently into the corners of her thoughts. Still, she pushed forward, using her new environment to rewrite the narrative that had been written for her by people who didn’t see her humanity.

Despite the progress of life and the stability the military provided, Bernice still had questions about her past. “That’s when my sister and brother decided to find our mother. She was an alcoholic. That’s why we were taken in the first place.” Even as adults, the relationship with their birth mother was strained and unpredictable.

Bernice reflects on her journey with clarity and deep internal conflict. “There was good and bad. The good was that I think God was always there. There was always church. But there was also the fear — the fear of being moved again, the fear of being separated. And when that did happen, I fell into depression.”

I had the fear of God, but I also had the fear of moving.

Bernice Hayes

Her story resists simple labels like “survivor” or “victim.” It’s layered — rich with resilience, faith, and quiet rebellion against being defined solely by circumstance. Her experience speaks to mid-20th century child welfare practices, yet it mirrors the struggles of today’s youth still navigating a system often unprepared to meet their emotional and mental health needs.

Though forgiveness didn’t come easily, Bernice eventually returned to some of the homes with her children — a personal attempt to confront her past and lay some memories to rest. Still, the scars lingered. Depression followed her into adulthood, first masked by alcohol and silence, later erupting during mental health crises that deeply affected her children.

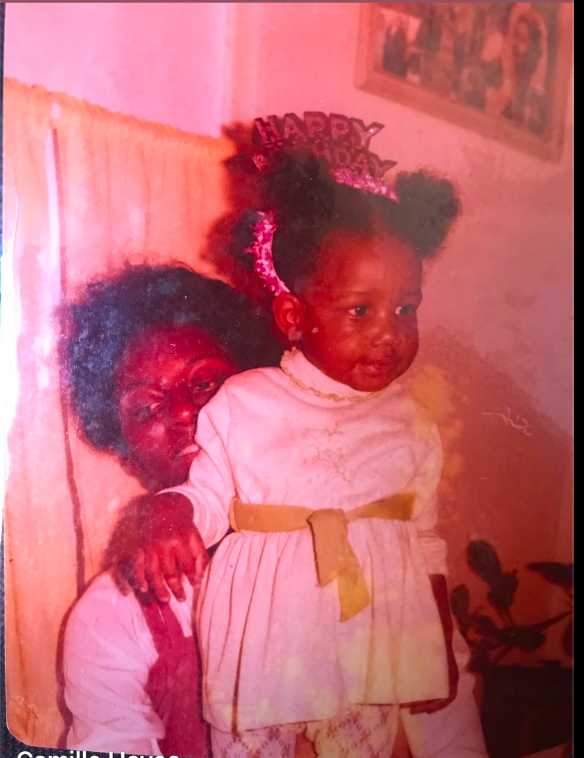

Her daughter Camille remembers the confusion of growing up with a parent battling invisible pain. “I was angry when she’d go to the hospital because I didn’t understand. But I started playing back all those stories and I had tremendous empathy for my mother.” Camille’s reflection speaks to a deeper understanding she reached as an adult — and the advice she wishes she could have given her younger self: “I wish I would have had a better understanding of grace growing up. I would’ve given my mom more grace when she was struggling, especially when mental illness took over her life.”

I wish I would have had a better understanding of grace growing up. I would’ve given my mom more grace when she was struggling, especially when mental illness took over her life.

Camille Hayes

Through the years, Camille learned to listen to her mother’s stories. “I used to allow her to tell me her stories, even at a young age. She would try to be age-appropriate, sharing things and I understood the importance of hearing her testimony, even though I didn’t always understand it.”

Camille’s perspective now is shaped by both her mother’s pain and her resilience. “Try to have understanding and offer support when you can. It’s hard being a parent, especially when you’ve never had someone to show you how. But I know now that my mom’s strength – despite everything she went through – was a testament to the grace she gave herself to keep going.”

Try to have understanding and offer support when you can. It’s hard being a parent, especially when you’ve never had someone to show you how. But I know now that my mom’s strength – despite everything she went through – was a testament to the grace she gave herself to keep going.

Camille Hayes

Bernice’s eventual victory was hard-earned. After years of struggling, she achieved one of her greatest dreams: earning her college degree. Together with Camille, they graduated from Geneva College, and later, Bernice earned her social work degree. Today, she is a social worker herself, helping others who face the same struggles she once did.

While healing is a journey – one that Bernice is still on – it has brought her peace. She knows that forgiveness, though difficult, is crucial not only for reconciling with others but for one’s own peace of mind. Bernice, reflecting on the journey toward healing, says: “Forgive, for your own healing. Do it for yourself because, like they say, ‘Forgiven people forgive people.’

Forgive, for your own healing. Do it for yourself because, like they say, ‘Forgiven people forgive people.’

Bernice Hayes

That message, both from Bernice and Camille, is one that anyone can carry with them — healing is possible, but it starts with grace and forgiveness, even when the past seems too painful to face. Bernice has learned to give herself that grace, and to extend it to others, even when it hurts. “If I could say something to the youth aging out of the system today,” she says, “I’d say develop a trust with your social worker. Speak up safely. And most of all, I am still learning to trust in my God, the Creator of us all, to develop a habit of talking to Him, and having an attitude of gratitude.”

Faith has played a central role in her healing. She recalls, “When it’s time to leave home, you should have a plan. You may need help from some trusted adults, agencies — and know that God has said, in Jeremiah 29:11, ‘For I know the plans I have for you… plans to give you hope and a future.’ Remember now your Creator in the days of your youth.” Her words, grounded in Scripture and hard-won wisdom, offer not just advice — but hope.

Together, Bernice and Camille’s voices shed light on long-term mental health effects — particularly for those who grow up in care. For every child placed in a home, there is a need for more than just shelter. They need safety.

And yet, healing is rarely a straight line. Bernice fought to survive, to parent, to grow. She became a woman of resilience — working, raising children, finding faith, and facing her past, piece by piece. Today, she reflects on that past not with bitterness, but with a desire to represent herself and her foster families in a better light. “As I learned,” she shares, “it is my desire to speak the truth in love — because only then can we grow and become the mature body of Christ.”

This May, we’re not just raising awareness. We’re amplifying lived experiences. Let this be a call to listen, to believe, to support, and to act. Because healing is possible. And every story — like Bernice’s — deserves to be heard.