Blog

Loving Her in the Skin She’s In

How a grandfather’s unconditional love for his LGBTQIA2S+ granddaughter fosters family and community acceptance

Coming out LGBTQIA2S+ (i.e., Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and/or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, Two-Spirit) is—or always should be—a personal choice.

For most LGBTQIA2S+ youth, the coming out experience and/or living as an LGBTQIA2S+ person also involves family. While there have been multiple LGBTQIA2S+ reports and stories in the traditional foster care system, for youth and families in the kinship space, the situation is and should be seen differently.

Empowering families in kinship care has much to do with providing choice, as we believe decisions must remain within the family constellation and not be facilitated by the system. In the same way, it is a youth’s choice how they identify. And LGBTQIA2S+ youth have a choice whether to come out and how they come out. Our role is to meet youth and families where they are and provide a pathway that is affirming and supportive, and to provide services and resources the family may seek.

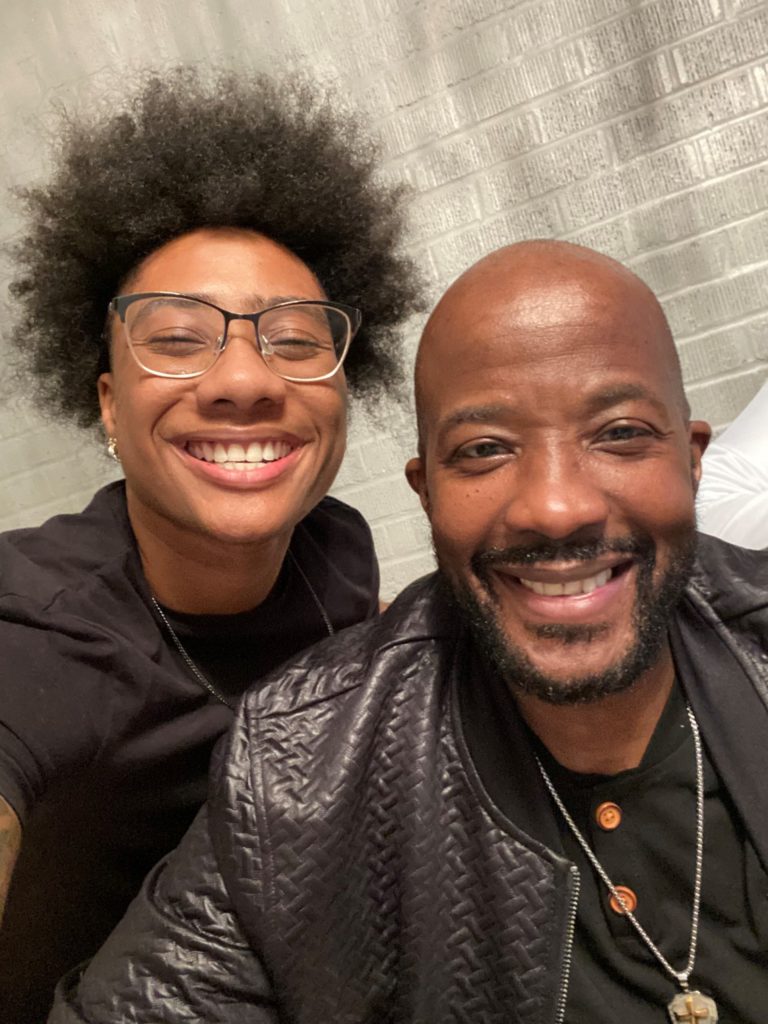

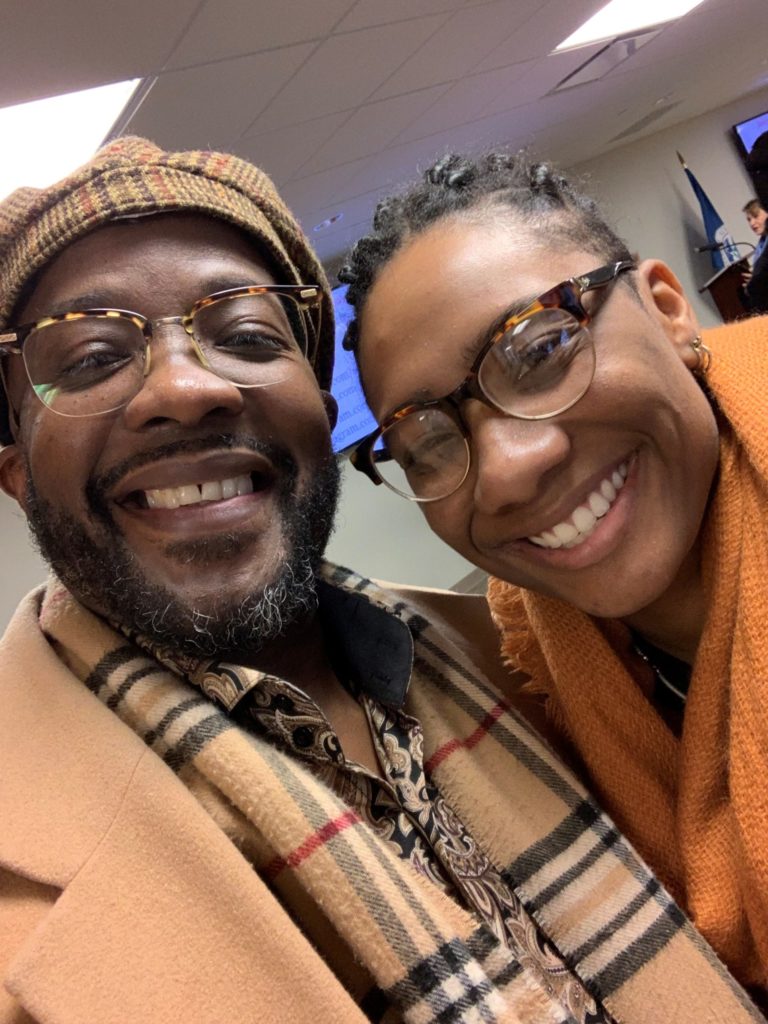

For Dr. David Brock, former kinship caregiver and ASCI’s Managing Director of Family and Community Engagement, maintaining an atmosphere of love at home—something innate to his character—has been instrumental in ensuring a safe and supportive environment for his granddaughter, Shauna Josephs.

Identifying as a young woman with diverse SOGIE, Shauna relied on the love and support of family to help navigate the cultural stigmatization she had feared as a child in Jamaica.

Faith, Family and Acceptance

“At a young age, I did know [I was gay],” Shauna says. “It was a lot harder being Jamaican and Christian at the same time. When I moved here, I was about six or seven years old, and as I grew older…I would pray to God every day that I could change…ask God to take it away. As I got older, nothing changed, at all. So, I kind of always knew.”

As a pastor in the Christian faith, Dr. Brock has taken a firm stance against all hate and judgement cast upon the LGBTQIA2S+ community, and stands in love and solidarity with his granddaughter, proudly supporting her at all times.

“She actually doesn’t even know this, but she literally changed my view as a man of God, as a pastor, in a lot of areas that I had some hang-ups,” he shares. “And because of her, if you ever walk in our church, there’s a big banner on the wall that says, ‘No Judgment Zone.’ It was because of her and her brave ability to come and say, ‘Pap Pap, I’m different. This is who I am.’ I have worked for the last few years really trying to instill in the people at Love Fellowship Church that it’s really about love.”

“The ‘No Judgement Zone,’ I love that,” Shauna chuckles. “Every time I go in there, I look at it. I show my friends when I bring my friends, or my family, my cousins… it’s like my favorite thing.”

“I wanted her to come to church and be able to say, ‘I’m safe at church. That people aren’t looking at me, judging me because they don’t necessarily agree with where I am or where I’m walking,’” Dr. Brock continues. “You know, my biggest thing I asked [Shauna] was, ‘Are you willing to keep doing the work to become the best you can be?’ She told me, “Yes,” I was like, “I’m good with it. I’m good with it. As long as you’re willing to keep growing to become the best you that you can be, I’m good with it.” So, I had to try to educate people at church. This is not our job, to judge the rightness or wrongness. It is our job to love people.”

At the age of 18, Shauna found the courage to come out to her family despite being fearful of their response. “All I can say is, it was rough,” she shares. “It was rough coming out, telling my dad, and it was rough coming out telling my biological mom. Like I said, being Jamaican and being a Christian, it’s just not what’s right to them.”

While many family members were receptive—especially her Pap Pap—Shauna didn’t initially feel safe enough to be herself.

“I left home,” she admits. “I remember it was Christmastime. I had just come out in the fall. Things were still rocky, and I didn’t know if I was accepted. I didn’t know if home was a safe place to be. I didn’t know if I was wanted. So, I ran away. I left with my best friend, and we drove all the way to Altoona to spend Christmas with her family.”

Dr. Brock expresses that, while he cannot protect Shauna from the judgement of the world, he’s made sure that his home will always be a place of refuge through the love of their family.

“It really caused me to say, ‘There has to be an environment where I’m not telling you what’s wrong with you, but I’m trying to tell you to be the best you can be, and to love that individual” he says. “I don’t see anybody except my granddaughter. That’s all I see. And I look at her from that place of love. But still, there’s a part of me that can’t keep her safe like I want to, because of those out there who have such cut-and-dry views. It’s right or it’s left, in or out, up or down, over or under. There’s no gray. There’s no middle ground. There’s no negotiation. There’s no place of acceptance. That’s my biggest thing—I have to do what I can to keep her safe. That’s all that matters to me. I know Shauna just wants to be able to be Shauna. She wants to come to the cookout and be Shauna. She wants to come to church and be Shauna. She wants to go to work and be Shauna.”

So, who is Shauna? Now in her late 20s, Shauna works as a CNA at a nursing home, assisting older residents on the rehabilitation floor. When they arrive from the hospital, Shauna helps them get them recover and get back in shape. For fun, she spends quality time with her seven younger siblings. “I love hanging with my siblings,” she says. “They’re literally the most important people in my life. So, any chance I get, I like being with them. All together, they’re my brothers and sisters. There’s no stepbrothers. There’s no stepsisters. There’s no step granddaughter. There’s none of that. It’s family.”

But not everyone can see individuals so holistically. “Look at me…that’s what people are gonna see,” Shauna explains. “They’re just gonna see, ‘Oh, she looks like a little boy.’ That’s what I’m used to. But that’s not what I am. That’s not who Shauna is. But I just go with it, especially if it’s people I don’t know. I don’t need to explain anything. All I care about is my family and my close friends.”

And her Pap Pap agrees! “I just see Shauna. I don’t see a tag on her forehead that says gay, lesbian, whatever. I just see Shauna…everything she is, I just see Shauna” Dr. Brock says. “And the love that I have for her wants her to be the best Shauna she can be.”

“I just see Shauna. I don’t see a tag on her forehead that says gay, lesbian, whatever. I just see Shauna…everything she is, I just see Shauna.”

Dr. Brock

And this holistic acceptance creates an environment of safety in Dr. Brock’s home and church. “Perfect love casts out all fear. In other words, when a person comes into an environment where they feel loved, they become less fearful to be themselves. They become less fearful to unveil and let you in.”

Applying What We’ve Learned from Dr. Brock and Shauna

While LGBTQIA2S+ youth comprise only 11% of the overall population, they are represented in the child welfare system at a rate of 30%, according to a 2019 study. The Center for the Study of Social Policy explains, “Youth identifying as LGBTQ are overrepresented in child welfare, and they experience higher instances of homelessness, poor educational outcomes and youth probation.” So, consider the implications for LGBTQIA2S+ youth in care if the system focused on building and nurturing family acceptance; ensuring youth’s child welfare experiences are empowering and affirming; and connecting youth to supportive LGBTQIA2S+ peer groups.

As a grandfather who has had to learn to break down the barriers of his own biases, Dr. Brock advises other caregivers and parents to do the same by asking themselves questions to get to the root of their reservations.

“First of all, acknowledge what you see,” he begins. “What you see is real. You see it before [youth] come out. Would you love them any differently if they never came out? You’ve got to ask yourself that. Is their coming out going to change how you love them, how you see them? Would you treat your biological child any different than you’re treating this child?

“It’s your struggle with acceptance, and you’re forcing your issue on them. You’ve got to grapple with your own issue. You have to [ask yourself], ‘What is it about this that I can’t accept? What is it about this that I don’t like? What is it about this that’s really turning me off? Is it religion? What is it?’”

Megan Martin, Executive Vice President, Center for the Study of Social Policy, and primary author of Out of the Shadows, explains the importance of parents and caregivers creating a safe home environment for children and youth in general as a means of open communication.

“It is important to promote open communication in safe ways and to ensure that families have the information they need to better understand identity development,” she explains. “I think there is oftentimes an inclination to break up a youth’s identity. There is this idea that, there is this part of a person, and that part of a person, but that is not how we feel as people. All aspects of our identity are intertwined.”

“I think there is oftentimes an inclination to break up a youth’s identity. There is this idea that, there is this part of a person, and that part of a person, but that is not how we feel as people. All aspects of our identity are intertwined.”

Megan Martin

When working with families, Martin says we should be making sure they have the support and resources they need behind them so that all young people are supported, and all families are equipped to support, a young person by accepting their entire identity.

“If we take this approach, we demystify identity a little bit” she says. “We keep [sexual orientation and gender identity and expression] from turning into something that families are worried about or afraid of and turn it into a regular part of how we promote the health of young people. Too often, it becomes something that we do not address as a holistic part of health and development. We address it as a problem to solve, and then young people feel it is a problem as opposed to a part of their identity and their health.”

Another aspect of creating a safe environment is to go at the youth’s pace. Martin shares that one of the things she often hears directly from young people is that we should not push them to disclose information about their identities, but simply make it clear that you are open and nonjudgmental if they choose to disclose. “Sending those cues to kids is critical in helping them feel safe, even if they do not have anything they want to disclose to their families,” she says.

At times, it may be challenging for families to understand or even relate to children and youth who identify with diverse SOGIE, however, if they have a willingness and openness to understand, education is often the first step they can take toward acceptance.

Angela Weeks, Project Director of LGBTQ Programming for the Institute for Innovation & Implementation at the University of Maryland, explains, “Caregivers can attend interventions to teach them how to process their own biases around this population and to help them learn affirming behaviors.”

“The last thing we want [Shauna] to do is to go out in this world, feeling like she has nobody in her corner,” Dr. Brock adds.

Weeks explains that LGBTQIA2S+ youth report poorer treatment while in foster care, are placed in residential facilities at higher rates, and experience more instability while in care compared to their non-LGBTQIA2S+ peers. “We also know that there is a lack of reunification programs that focus on LGBTQIA2S+ related family conflict being implemented. There are also no evidence-based programs that work with families on building affirming behaviors, which means that of the programs that do exist, they don’t have access to funding reserved for EBPs (like Families First). Also, many young people will come out in their teens, so teenagers in general are more likely to linger in care without adoption or stable foster homes. At the end of the day, much of the barriers to permanency come down to anti-LGBTQIA2S+ bias.”

“For youth, they deserve support and affirmation for all their identities. They deserve to hear that they are wonderful and that there is nothing wrong with them. They deserve all the things that non-LGBTQIA2S+ youth have, like excitement around their first date or inclusive-positive sex education.”

Angela weeks

Weeks suggests an intervention that goes beyond training—a group clinical/coaching model called AFFIRM Caregiver. The intervention walks caregivers through eight sessions that explore early messages, internalization of those messages and ways to change behavior over time. “Caregivers who have completed this intervention with us have left saying it’s changed the ways in which they view the world,” she offers. “For youth, they deserve support and affirmation for all their identities. They deserve to hear that they are wonderful and that there is nothing wrong with them. They deserve all the things that non-LGBTQIA2S+ youth have, like excitement around their first date or inclusive-positive sex education.”

Weeks additionally emphasizes the value of a peer community. “Finding spaces with other LGBTQIA2S+ young people is so important,” she explains.

Shauna can relate: “I definitely feel as if I fit in better with my gay friends than my straight friends. I feel more comfortable around them. I could talk to them about things that you can’t with your straight friends. I mean, at the end of the day, your friends are your friends, but there’s a different level.”

“If you can find mentors, that’s also great,” Weeks continues. “A lot of young people are unsure of whether they can have a normal and healthy adulthood, and mentors can be the possibility model for them. The more relevant the support group or community group is to the other youths’ identities, the better. If you have a Black transgender youth, finding a Black transgender support group could be life-changing.”

Weeks also suggests youth interventions that can help build coping skills and increase self-esteem. Journey Ahead is a program of the Ruth Ellis Center, and it is an adventure therapy program that helps build community and coping skills. Also, similar to AFFIRM Caregiver, there is another evidence-based intervention called AFFIRM Youth that helps youth with a number of life skills. AFFIRM Youth is the only LGBTQ EBP for youth of which Weeks is aware. She suggests child welfare agencies look into what already exists that is having a positive impact and try to bring these programs to our organizations.

“Preparation should be happening early and often, and normalized, and a part of just thinking about health and supporting a young person to be successful, which is what everybody wants,” Martin offers. “We all have the same goal: supporting healthy and happy young people. We have to work together early on, so that when young people address issues of their identity, we [don’t contribute] to any trauma that young people have already experienced—the trauma from the oppression in the world, racism, the trauma of being removed from their parents, and then potentially the trauma of being rejected by other family members—which would be so harmful to any young person for any reason.”

Weeks believes hotline workers need training on the risks associated with anti-LGBTQIA2S+ rejection, because in many cases, they might not associate it with abuse or neglect worthy of investigation. Then, the workforce needs to have the knowledge to assess when LGBTQIA2S+ identities are a source of family stress and conflict. “If it is a source of conflict, [caseworkers] need to know how to support that youth and family in different ways (e.g., coming up with a safety plan if the youth wants to disclose their SOGIE to others, or helping youth get affirming medical care),” she suggests. For families, it could be getting them connected to family intervention programs like the Family Acceptance Project or the Youth Acceptance Project. Both of these programs consist of clinicians who are specialized in the journey a family goes through when their child comes out, and they both provide clinical support to the family, along with coaching and education on supportive behaviors.

“This is where kinship is really so important…to foster relationships that are healthy and supportive, where kids can find permanency with their families in homes that respect and love them,” Martin says. “For kids who face oppression and structural racism in the world and then come to [the child welfare] system that is also oppressive and racist…this of course creates a barrier to permanency for a lot of young people. But I think, again, it comes back to fostering relationships with families who are supportive and caring and loving and permanent. “

Fortunately for Shauna, she has found such loving and permanent support. Dr. Brock shares, “I asked her [the night she came out], ‘Did you expect something to change? I’m gonna love you just the same.”