Blog

Foster Care Month: Real Talk with System Alum Ivory Bennett

Foster care alumna Ivory Bennett spent the majority of her early life in foster care until aging out while in college. “I spent about 17 years in foster care in Western Pennsylvania,” she explains. “But I was in foster care so long because my mother had extreme mental illness. She had bipolar disorder— she still has bipolar disorder—schizophrenia and a few other things, and my father was missing in action. I spent the majority of my time in foster care with my younger sister, Ebony. We were in foster care for the majority of the time until she was sent to a group home after living in a kinship care home with me and my aunt.”

“I know that when I was first born, I was not with my mom and I was not with a biological relative,” Bennett continues. “But I don’t think I was formally in any kind of care. I was with a woman who was one of my grandmother’s best friends for some time while I was an infant. I believe I formally entered foster care around the age of four or so, and I stayed in until I aged out when I was in college.”

The most important thing anyone can do to make life better for foster youth, especially if they themselves are foster youth, is to heal. I have been really intentional about healing myself. My childhood traumas, my parent wounds, my family wounds … acknowledging that I am hurt. Acknowledging that it is OK to be hurt because

I am a human.

Bennett explains that although she perceived many people to care about her situation, she did not receive the full support she needed while in the child welfare system. “To be honest, I don’t remember conceptually having an understanding of the foster care system until I was a teenager or a preteen. As a child, I knew that I was at court. I knew that I was a foster kid. I knew that there were lawyers and judges who were making decisions about my life. I knew that if I wanted to say something that I could, and I wasn’t afraid to do that. But I’m not necessarily sure that I felt supported or that I could ask for things that I wanted and needed.”

However, those who were behind her had a lasting impact. Bennett continues, “As a teenager during my independent living time, I had an amazing set of advocates and workers. My independent living worker was amazing, her supervisor was amazing. I love them both, and they both still communicate with me to this day. I felt connected to people who had my back and supported me. But there were a lot people during my independent living who I encountered who really made me question their motives in the way they treated me or others, the way they had favorites, and the way they allocated resources. To see the nasty side of foster care was discouraging, but it was also motivation to become an advocate and to fight for the things we need.”

Looking back, Bennett questions why there was no permanency plan for her and her sister despite the many professionals they encountered. She explains, “In some regards, you can say people knew us so much from our interactions frequently with the court that it kind of helped us in a way—it was somewhat advantageous given the circumstances—but then in a lot of other ways, [I ask myself], why wasn’t there some type of permanency plan in place to help us deal with everything that was going on? How did we end up in so many different homes with so many different placements on and off again?”

Bennett continues, “I was in about four kinship care homes throughout my entire time in foster care. I lived in about 10 other homes (nonrelative) and one shelter. I attended about 12 different schools in three different counties.” Bennett explains that such “numbers” can be impactful in informing change to the child welfare system. “While working with one organization, I came up with a grant idea and we developed a street team. One of our tactics for telling our story and creating awareness for foster youth was [using] our numbers, because people were so amazed by how many different homes and schools and families and settings foster youth at that time had been in and were able to speak about.”

Today, as an English teacher, Bennett values education and understands the importance of children developing literacy skills at an early age. “We know that statistically, by third grade, if students don’t have a grasp on literacy, they’re likely to spend the rest of their lives illiterate,” she says. “There was only one year of my life in schooling before 7th grade where I was in the same school for the entire school year. It’s shocking and a shame that I was only given one year in the same place to study to get what I needed for my future scholastic success. And I can’t say that my younger sister had the same results or opportunities that I had in terms of schooling.”

Despite the many challenges she faced, Bennett remains optimistic that positive changes are happening in child welfare and is dedicated to advocating for this change.

“I’m trying my best to be involved with foster youth,” she begins. “I love foster youth. I really just want the best for them, and I can totally understand where they’re coming from. I feel that to whom much is given, much is required. And, although my life has been hard, I’m a very blessed person and I’ve been given a lot. I really want to return that back to the people who need it the most. Whether it be formally or informally, I will continue to advocate on behalf of foster youth for my entire life. I’m positive that the changes that need to happen will happen. We just have to keep trying, believing, supporting, and showing up and being present.”

Some of the changes for which Bennett advocates include bettering options for foster youth to reach permanency. “Things are happening, but things need to happen in a more intentional way. It’s wonderful that we have such intense permanency plans in PA, but we need to be more intentional about where we are placing children for the sake of permanency. It’s great to have such an ambitious goal of not letting kids sit in the system for more than a year and a half or two years, but I personally know several children who have been adopted or reunified with their families and birth parents and for whatever reason, they end up back in the system.”

She continues, “I personally think that’s more devasting than helpful. I can’t imagine what it would feel like to be a child and to think, ‘This is it, I’m home now, I can be safe and let my guard down now,’ only to end up right back in the same situation that they just left. And, I think it’s more of a policy and procedure thing. We need to vet these homes—whether they be foster homes, or adoptive parent homes, or even a biological home or family homes—we need to vet them better. We need to train workers better. We need to have more money invested in the process that evaluates their fitness for being in a permanent place of residence for these kids who are already highly subjected to trauma and need a lot of support and emotional intelligence in order for them to live their best lives.

“But I definitely think we need more leadership of people of color, particularly black women, in the city of Pittsburgh, because the demographic of foster youth in Pittsburgh is so heavily black. We need people who can run these organizations with lived experiences and pedagogical compassion.”

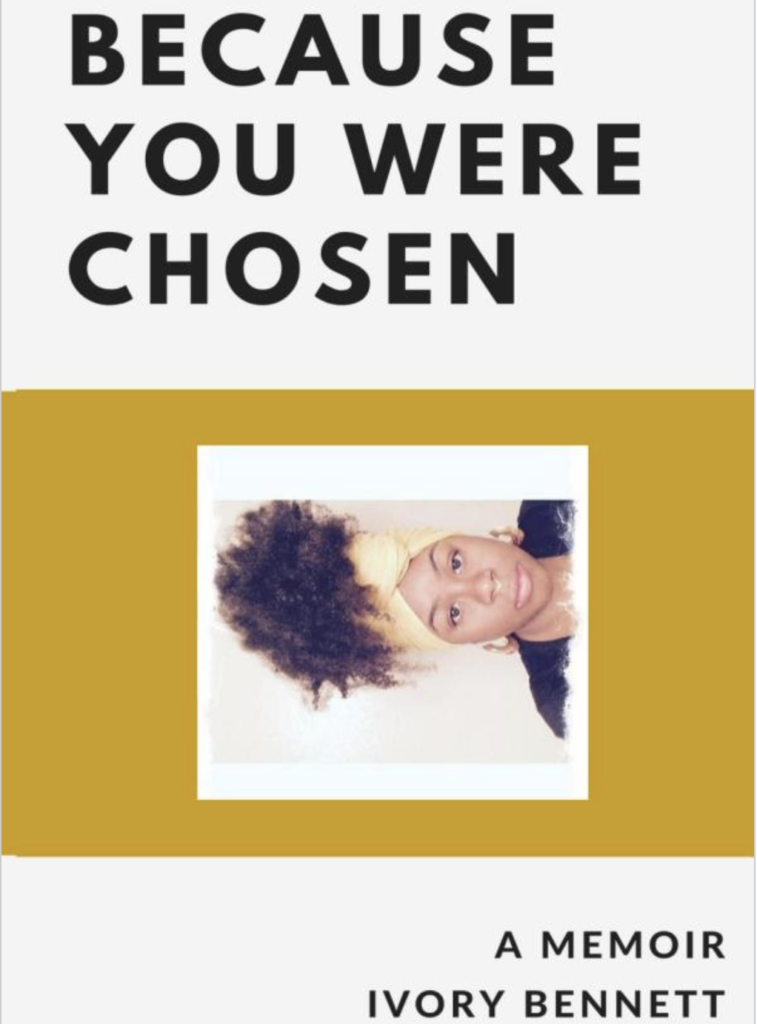

Bennett actively advocates for current and former foster youth as a 2020 National Foster Youth Institute Congressional Delegate and foster care alumni mentor with Fostering Change Network. In addition to writing and publishing her book, Because You Were Chosen, Bennett has recently established her own LLC, Ivory Co., focusing on the needs of foster care alumni.

She believes the first step toward advocacy as a foster care alumni is through healing. “The most important thing anyone can do to make life better for foster youth, especially if they themselves are foster youth, is to heal. I have been really intentional about healing myself. My childhood traumas, my parent wounds, my family wounds. Acknowledging that I am hurt. Acknowledging that it is OK to be hurt because I am a human,” Bennett shares.

“In order to heal, we need to feel. So, healing has been a really intentional choice and manifestation in my life, and that is where I begin my work and advocacy for current and former foster youth.”

Utilize all the resources available to you. Also, get the therapy you need now so that you do not internalize the things that happened to you. None of it was your fault. You are deserving of love, happiness and health. You have access to those things that can help you do that right here, right now. So get them done.

Listen before you speak. And be intentional about the words you use, because not everyone is going to be emotionally intelligent enough to understand your pain and look past it. Know that anything you want to be, you can be, as long as you work hard and you’re smart about the things you do.

You are human. Because you are human, you need to show yourself the same love, grace and compassion you show to others. Be about that life, in terms of extending yourself grace, because you want to extend it to others, so extend it to yourself first. Baby Ivory, you need to give yourself love, grace and compassion. It’s OK to fail. It’s OK to not know what to do next. It’s OK to ask for help. You don’t have to be perfect.

Ivory Bennett is a self-published author with a sincere passion for the creative arts. She has a dual degree from the University of Pittsburgh in Africana studies and English literature with a minor in theater arts. She is currently enrolled at Concordia University where she will graduate in December with a master’s in education administration with a principal cortication; concurrently, she is a student at Texas A&M University – Commerce, where she is completing her professorship credentials.

Bennett currently works as an English teacher and cheer coach. Outside of work, she has a strong commitment to volunteerism via her roles as a teacher ambassador with Give More HUGS, a foster care alumni mentor with Fostering Change Network Foundation, and as a 2020 National Foster Youth Institute Congressional Delegate. In her free time, Bennett loves experiential learning and being immersed in other cultures – she has a goal of visiting a new foreign country every year of her life – which is how she met her fiancé. She eagerly awaits her wedding and buying a French bulldog puppy.