Blog

3 Thought Leaders Explore the Black Family Experience in Child Welfare Through a Racialized & Historical Lens

A letter to the new White House administration by Dr. Sharon McDaniel, Dr. Ervin Dyer and Dr. Yven Destin. An edited version was originally published in the Imprint.

Dr. Sharon McDaniel

Dr. Ervin Dyer

Dr. Yven Destin

America holds onto an undemocratic assumption from its founding: That some people deserve more power than others.

—Jamelle Bouie

Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris,

During your campaign, I saw your signs touting the phrase, “Our best days still lie ahead.”

But what do “best days” look like for our children and families? When I look at the disproportionate impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on our Black and Brown communities, I am disheartened and discouraged. I can’t help but think, with a heavy heart, about how this latest public crisis has and will continue to impact children in the care of their kinship relatives and children removed from their birth parents by child welfare services.

The faces of child welfare for Black families in America can be seen in a grandmother struggling to help her grandchild cope with trauma; a cousin learning about the effect of domestic violence on her kinship child; an aunt trying to maintain her work schedule when she must pick up her infant nephews from different daycares…if children in these Black families and others are to receive the best care depends on how a responsive, 21st century child welfare system navigates racism, sexism, and classism.

As CEO of a nationally recognized kinship care service agency, a Black mother, and a former child of the system, I can say issues of racism remain problematic in child welfare services. I’ve dealt with the system and poured through the research on the overrepresentation of Black families in child welfare services—a system embedded with a racist ideology. Getting to the “best days” of child welfare in 2021 requires nothing less than dismantling the old system, centering Black families at the heart of kinship care policy, and having a transformative discussion on what we need to know so we can move forward from a race equity lens.

Frankly, there has been a longstanding assault on Black families. Since the birth of the United States, Black families caught in America’s child welfare system have experienced poorer outcomes than whites: They receive more limited services, are reported to authorities more often, are more likely to have case reports substantiated, spend longer periods in the care of others, are less likely to be adopted, are less likely to be reunited with their parents, and have more difficulty legitimizing adoptions.

These dire consequences of being Black spring from a racist ideology rooted in the origins of the system—an ideology that the New York Times’ “1619 Project” fully illuminates. For Black families and their children, this racist practice of family separation was initiated in 1619, consecrated in 1776, and reinforced by the U.S. Constitution signed in 1787. These dates showcase events that set in place a power structure and ideology in child welfare that rendered white lives superior and Black lives invisible. It created a child welfare system for white lives that first neglected and later destroyed Black lives. These events empowered and legitimatized a racist ideology that energizes the child welfare systems we still encounter today.

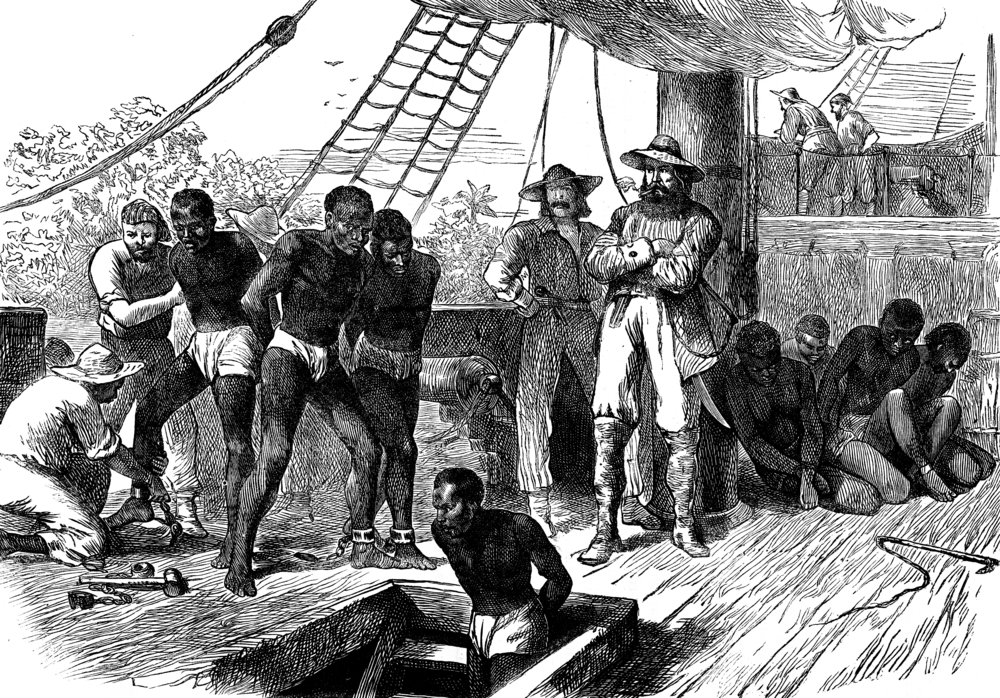

The year 1619 marks the moment the first enslaved Africans arrived in colonial Virginia. Slave auctions became the site of many a Black woman screaming as her baby or child was ripped from her arms. As one former slave shared, “Night and day, you could hear men and women screaming…ma, pa, sister or brother…taken without warning…People was always dying from a broken heart.”

Nearly 200 years later, in 1787, the separation of Black families became the crucible that helped unify the 13 original American colonies to create the United States as it is today. Per Constitutional Convention delegate James Madison’s notes, delegates from the northern states, desperate to create a nation, secured provisions that allowed the slave trade—and separation of Black families—to continue for another 20 years. And even though no new slaves were permitted to be imported to the United States, signing the provision into Constitutional law safeguarded the practice of Black family separation in building bipartisan agreement on the profitability of slavery in the land of the “free.”

The American child welfare system that emerged through slavery in the 19th century ignored Black families, whose welfare was at the discretion of white slave owners. Amid the cruel separations that went on across America, Black families tried to maintain the family unit. They practiced a form of community parenting through kinship, based in African traditions of social responsibility for children—a sort of informal child welfare network. According to Jiminez (2005), “women, for example, were mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts, and cousins to many others,” and fomenting an extensive kinship network was how Black families survived under slavery. After slavery was abolished, and under the force of racial segregation, Black families were left on their own, relying on kin for informal child assistance.

The child protection movement during the Progressive Era reforms (1890s-1920s) led to the withdrawal of children from the workforce and shifted parental obligations to children

toward the development and well-being of the child. There was no similar evolution when considering how the Black community felt the same obligations and concerns for the well-being of its children. Therefore, since slavery, Black families have been at the mercy of a largely white, racist system that essentially continues the practice of racially unjust family separations. Child welfare services are literally attacking the Black kinship system—the African tradition Black Americans have preserved to protect themselves against white assaults on their family lives.

The key to assisting America’s Black families in 2021 and beyond is to strengthen the collective responsibility they feel toward their own children. “These are historical and cultural traditions that African Americans have sustained in the period when they were excluded from the public welfare system” (Jiminez, 2005). As such, the following should be considered:

- Address child welfare ideology deliberately. We must become better able to quantify and qualify the role of ideology when interpreting legislation that impacts children and families.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) must fund a study on the interpretation of federal legislation and state policy. Such a study would yield a report not on what states are doing, but why. The question that must be answered is, in modern child welfare, does the guise of white middle-class morality remain the compass?

- Acknowledge the impact of ideology on the implementation of legislation.

- Require each state plan for child welfare services to describe levels of family empowerment and touchpoints of community engagement.

- Increase state accountability on racial justice in child welfare.

- Require each state plan for child welfare services to document specific efforts to address racial-justice efforts. While racism connects to our morals and values, acknowledging it does not automatically support race equity. Are you operating from a lens of cultural congruence and relevancy? Does data support equity efforts?

- Dismantle the Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA) of 1994, amended by the Interethnic Placement Act (IEPA) of 1996, which fuels the flames of racism in the system. Under this policy, when foster families are found, more children are transracially placed than placed in homes where they have greater racial congruency. However, research shows children experience greater well-being and more positive outcomes when they remain connected to their racial heritages.

- Use the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 as a guide to: acknowledge the over-surveillance of Black families in the child welfare system; place Black children in racially and culturally consistent homes by prioritizing kinship care; and involve a child’s family and community in service planning.

- It is important to note that better oversight is needed to ensure the efficacy of such policies. According to NICWA Executive Director Dr. Sarah Kastelic, “ICWA is the only federal child welfare law that doesn’t require specific data elements to be collected and for which there is no periodic review.”

Simply getting better will not end issues of disproportionality and over-surveillance of Black and Brown families; getting things done will. Child welfare reform begins when we acknowledge and believe that the activity of child welfare is shaped by ideology. This ideology is not obvious to families, but it is an ideology that not only pervades the child welfare system, but also creates what Neal Lester described as a system of privilege, creating a “hierarchy value”—where white people’s worldview is valued over that of Black people. While there will always be ideological differences, constructive controversy will make things better for children and families. These critical conversations let us discuss what we know to be true and what we believe to be true in child welfare.

As we move into 2021, the nation is still ideologically divided on family separation and kinship care—a matter we have yet to confront as a hard truth—and this is where we lie. The structure of the child welfare system continues to protect and reproduce the thoughts and ideology of those who created the system. Our nation has been presented with this kinship strategy since 1619.

In 2021, the emphasis can no longer be on protecting the system. Child welfare is about protecting children, as well as their moral right to be with their own families. We cannot wait on this. As a nation, we will always be engaged in some type of healing because the world is not equitable. But as scholar Andre Perry recently wrote, “Healing isn’t about giving people more time to make themselves ready to accept policies that advance racial equity.” It is not about waiting. It is about moving forward. We did not give families time to heal in 1619, nor do we now, when the system takes children away from their kin. With today’s child welfare response, we cannot continue to lie in the bed the system has made. It’s time to get up; otherwise, nothing will change.

I would like to speak with the CEO of a second chance. Can you let me know how to contact her?